To make two bold statements:

There's nothing sentimental about a machine, and:

A poem is a small (or large) machine made out of words.

When I say there's nothing sentimental about a poem, I mean that there can be no part that is redundant. Prose may carry a load of ill-defined matter like a ship, but poetry is a machine which drives it, pruned to a perfect economy. As in all machines, its movement is intrinsic and undulant, a physical more than a literary character.

--William Carlos Williams

Selected Essays of William Carlos Williams., New Directions, 1969. p. 256.

Poetry is usually seen as flowery, superfluous, and useless, when it is anything but. As Williams point out, poetry is a machine of words. Like machines, poems contain only what is needed-- just as a gaming system with two disc drives would make no sense, a poem full of extra words lacks meaning. A poem is "pruned to a perfect economy," meaning all the extras words (what Williams terms "sentiment") are cut out and only what is needed is left.

Since poems strip away all but a few lines and have flexible structure, they require interpretation. Unlike a narrative or informational paragraph, where ideas follow a sequential order, lines in a poem can happen in any order. They are like spokes in a gear, and like a gear, these spokes all revolve around a hole-- a missing piece that must be added to make the machine work. This hole is the main idea of a poem, which is called a conceit. The conceit is never directly stated and must be inferred by the reader. This hidden conceit makes it a "complete" (or, as Williams calls it, "intrinsic") work.

The conceit in intrinsic to a poem because it is insolubly tied to the poem's structure. Just as different machines perform different tasks, different poetic structures relate different conceits. An analysis of a poem's structure is called prosody, and involves looking at the stanzas, rhyme scheme, refrains, meter, and volta to can determine what type of "machine" the poem is.

Since poems strip away all but a few lines and have flexible structure, they require interpretation. Unlike a narrative or informational paragraph, where ideas follow a sequential order, lines in a poem can happen in any order. They are like spokes in a gear, and like a gear, these spokes all revolve around a hole-- a missing piece that must be added to make the machine work. This hole is the main idea of a poem, which is called a conceit. The conceit is never directly stated and must be inferred by the reader. This hidden conceit makes it a "complete" (or, as Williams calls it, "intrinsic") work.

The conceit in intrinsic to a poem because it is insolubly tied to the poem's structure. Just as different machines perform different tasks, different poetic structures relate different conceits. An analysis of a poem's structure is called prosody, and involves looking at the stanzas, rhyme scheme, refrains, meter, and volta to can determine what type of "machine" the poem is.

Elements of Prosody

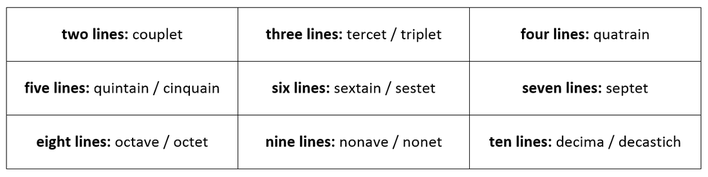

STANZAS: Stanzas are a series of lines grouped together and separated by an line break from other stanzas. The stanza is the main structural unit of verse, just as a paragraph is the main structural unit of prose. Stanzas are identified by the number of lines they contain.

RHYME SCHEME: Most poems use couplets, triplets, and quatrains in their construction. Determining the lines of a stanza is important to determining its rhyme scheme. A rhyme, or course, is a pair of words that use the same end sound, and a rhyme scheme is a pattern of rhymes at the end of each line that stay consistent over the course of several stanzas. Rhyme scheme is noted by capital letters representing a different rhyme.

If you can dream and not make dreams your master; A |

I should have loved a thunderbird instead; A |

Here are two quatrains, yet the Kipling selection has an ABAB rhyme scheme and the Plath selection has an ABAB rhymes scheme. If a stanza has no rhyming patterns at all (like if one of these examples was ABCD), then it has no rhyme scheme. Obviously, the more lines a stanza has, the more complex the rhyme scheme can be. Couplets only have AA rhyme scheme, while triplets are AAA or ABA. Yet quatrains have several varieties:

- BALLAD QUATRAIN: uses ABCB rhyme scheme and any meter

- ENVELOPE QUATRAIN: uses ABBA rhyme scheme and iambic tetrameter

- GOETHE QUATRAIN: uses ABAB rhyme scheme but has no constant meter

- HEROIC QUATRAIN: uses ABAB rhyme scheme and iambic pentameter

- HYMNAL QUATRAIN: uses ABCB rhyme scheme, iambic meter of 4-3-4-3

- ITALIAN QUATRAIN: uses ABBA rhyme scheme and iambic pentameter

- RUBA'I QUATRAIN: uses AABA rhyme scheme and any meter

METER: Notice that in the above list the ballad and hymnal quatrains, Goethe and heroic quatrains, and envelope and Italian quatrains have the exact same rhyme scheme, but are differentiated by meter. Meter refers to the pattern of syllables in a line of poetry. Just as a poem can have a consistent stanza and rhyme scheme, it can also have a consistent meter. A consistent meter gives a poem cadence, or a nice sounding rhythm. To determine meter, first determine how many feet are in a line. A foot is a unit of two syllables.

|

What happens to a dream deferred? 4 feet

Does it dry up 2 feet like a raisin in the sun? 3 feet + extra Or fester like a sore 3 feet And then run? 1 foot + extra --Hughes lines 1-5 |

That time of year thou mayst in me behold 5 feet

When yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang 5 feet Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, 5 feet Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. 5 feet --Son. 73 lines 1-4 |

Langston Hughes' "Harlem" has no regular meter: the first line is four feet, then two, then three with an extra syllable. Shakespeare's "Sonnet 73," on the other hand, definitely has a regular meter of five feet in each line. Here are terms for the number of feet in a line:

- TRIMETER: three feet per line

- TETRAMETER: four feet per line

- PENTAMETER: five feet per line

- HEXAMETER: six feet per line

- SEPTAMETER: seven feet per line

- OCTAMETER: eight feet per line

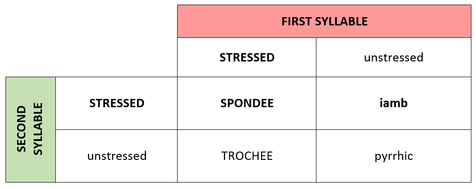

Thus, Shakespeare is writing in pentameter, but if we look closer at stresses, we can see further patterns. A stressed syllable is one that is emphasized, while an unstressed syllable is not. Think of this word: present. If it refers to a gift, the stress is on the first syllable and it becomes PRES-ent; if it refers to going in front of the class and speaking, the stress is on the second syllable and it become pre-SENT. Different feet can have different syllable patterns.

If the feet in a poem have a consistent pattern, then it can be said to be spondic, iambic, trochaic, or pyrrhic. Let's look at Shakespeare's pentameter again, this time putting all the stressed syllables in all caps:

That TIME of YEAR thou MAYST in ME beHOLD

When YELLow LEAVES, or NONE, or FEW do HANG

Every foot has the same pattern: an unstressed syllable followed by a stress; thus, Shakespeare's meter is iambic pentameter. Meter can have a variety of patterns. For instance, look at the following lines (stresses are bolded):

O, my luve's like a red, red rose, 4 feet

That's newly sprung in June: 3 feet

O, my luve's like the melodie 4 feet

That's sweetly played in tune. 3 feet

--Burns lines 1-4 (sic)

The pattern is iambic like Shakespeare, but the lines switch from tetrameter to trimeter. Even though there is not 100% consistency there is still a pattern, meaning it does have regular meter. evaluating that the rhyme scheme is ABCB, the best way to describe this poem is in hymnal quatrains.

Sometimes, a line in an otherwise consistent meter breaks that meter with an extra syllable, such as:

To be or not to be: that is the question. (Ham III.i.56)

Like all of his other works, Shakespeare wrote Hamlet's verse in iambic pentameter, but he added an eleventh syllable on this line. Does this mean his work is not in iambic pentameter? No, it's still iambic pentameter. Poets occasionally violate a consistent meter on purpose-- when the reader starts to follow the pattern, any break in the pattern adds emphasis and gets their attention. Sometimes a poet will switch out a foot with another type of foot or add an extra syllable to the end of a line (if the syllable is stressed, this is called a masculine ending; if the syllable is unstressed, like in this sentence, it is a feminine ending). Occasionally, you will find poetry where the extra syllable is a regular occurrence, in which case the poet has decided to use a rare three syllable foot, either an anapest (two unstressed followed by a stress, like in an-a-PEST) or a dactyl (a stress followed by two unstressed, like in MAR-mal-ade). Lines of poetry can also have a syllable missing from the beginning or ending-- these are called catalexic lines.

That TIME of YEAR thou MAYST in ME beHOLD

When YELLow LEAVES, or NONE, or FEW do HANG

Every foot has the same pattern: an unstressed syllable followed by a stress; thus, Shakespeare's meter is iambic pentameter. Meter can have a variety of patterns. For instance, look at the following lines (stresses are bolded):

O, my luve's like a red, red rose, 4 feet

That's newly sprung in June: 3 feet

O, my luve's like the melodie 4 feet

That's sweetly played in tune. 3 feet

--Burns lines 1-4 (sic)

The pattern is iambic like Shakespeare, but the lines switch from tetrameter to trimeter. Even though there is not 100% consistency there is still a pattern, meaning it does have regular meter. evaluating that the rhyme scheme is ABCB, the best way to describe this poem is in hymnal quatrains.

Sometimes, a line in an otherwise consistent meter breaks that meter with an extra syllable, such as:

To be or not to be: that is the question. (Ham III.i.56)

Like all of his other works, Shakespeare wrote Hamlet's verse in iambic pentameter, but he added an eleventh syllable on this line. Does this mean his work is not in iambic pentameter? No, it's still iambic pentameter. Poets occasionally violate a consistent meter on purpose-- when the reader starts to follow the pattern, any break in the pattern adds emphasis and gets their attention. Sometimes a poet will switch out a foot with another type of foot or add an extra syllable to the end of a line (if the syllable is stressed, this is called a masculine ending; if the syllable is unstressed, like in this sentence, it is a feminine ending). Occasionally, you will find poetry where the extra syllable is a regular occurrence, in which case the poet has decided to use a rare three syllable foot, either an anapest (two unstressed followed by a stress, like in an-a-PEST) or a dactyl (a stress followed by two unstressed, like in MAR-mal-ade). Lines of poetry can also have a syllable missing from the beginning or ending-- these are called catalexic lines.

REFRAIN, ENJAMBMENT, CAESURA: Sometimes instead of just repeating meter or a rhyme, a poem repeats an entire line:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

--Plath 1-9

This is called a refrain. Notice also in this poem that even though each stanza is three lines, the first is three different sentences, the second is one sentence, and the last is two sentences. In poetry, just because a line ends does not mean a sentence or thought is over. When a poetic sentence does not pause at the end of a line, it is called enjambment. But what about pauses within a line? Look at the eight line in Plath's poem: the comma after moon-struck indicates a pause in the middle of a line. A pause in the middle of a line of poetry is called a caesura. There are two types of caesuras: masculine caesuras come after a stressed syllable ("When yellow leaves, II or none, II or few do hang), and feminine caesuras come after an unstressed syllable (like the example in Plath).

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

--Plath 1-9

This is called a refrain. Notice also in this poem that even though each stanza is three lines, the first is three different sentences, the second is one sentence, and the last is two sentences. In poetry, just because a line ends does not mean a sentence or thought is over. When a poetic sentence does not pause at the end of a line, it is called enjambment. But what about pauses within a line? Look at the eight line in Plath's poem: the comma after moon-struck indicates a pause in the middle of a line. A pause in the middle of a line of poetry is called a caesura. There are two types of caesuras: masculine caesuras come after a stressed syllable ("When yellow leaves, II or none, II or few do hang), and feminine caesuras come after an unstressed syllable (like the example in Plath).

VOLTA: Finally, there is the volta. Volta is Italian for "turn," and the volta is the turn in the poem's argument or line of thought. Some poetic structures require a volta at a certain line: a Shakespearean sonnet has its volta between the third quatrain and the couplet, and a haiku has a volta in its last line. Other verse may have a volta anywhere or even multiple voltas. A strong indication of a volta is a sudden shift in the grammar of the poem, especially if a line begins with a coordinating conjunction. Look at the volta in the following villanelle--notice how the line with the volta starts with an abrupt dash:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster

--Bishop

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster

--Bishop

Specific poetic structures

While poets can play with a variety of structures, certain structures are used frequently. The structure of the these poems ties into conceit on a fundamental level: fore example, if a poem has fourteen lines, iambic pentameter, and a ABAB rhyme scheme ending with a couplet, it is a sonnet. Sonnets are always about love, so the conceit is some statement about love. Going back to the machine metaphor, different poetic structures are built for different conceits just as different machines are different tasks; just as a jackhammer cannot be used to cook food, a sonnet couldn't be used as a protest poem or a poem about nature. There are other distinct forms for that-- see the link below for details.

Analyzing a poetic work

Before analyzing a poem, you mus read it correctly. First, number each line. Poems are referenced by actual line of text, not by sentence. Next, read the poem aloud. Just as machines physically operate, a poems is meant to be physically recited. When listening to the poem read aloud, try to hear the rhythm of the poem and well as any wordplay or interesting sounds your voice makes-- all of this is intentional.

After reading, first determine the poem's structure. First, count the number of stanza and the number of lines in each stanza. Next, look for a regular rhyme scheme throughout the stanzas. Then count the syllables in each line and see if there is a consistent meter; if there is, analyze the feet and determine the exact type of meter. Look for repeated refrains and uses of enjambment and caesura. Finally, add all the elements together a determine the poem's specific structure:

Next, determine the conceit of the poem. The conceit is usually inferred and not stated and requires interpretation. Consider who the speaker is and who they are speaking to. Examine ideas and lines that are repeated throughout the poem. Look at what the specific structure of the poem is designed to engage: Free Verse, for example, is always about freedom or struggling for freedom, Haikus are always about nature, sonnets are always about love or heartbreak, and villanelles are always about personal loss.

Next, determine the style of the poem. What is the overall tone of the poem? What examples of imagery stick out? How does the imagery support the conceit? What interesting choices of diction are made (be specific with words)? Note: you do not discuss syntax--that is part of the structure section

Finally, critique the poem. Did the poet pick the right structure for the conceit? Is the poem stripped down to just what is needed, or as Williams calls it, "pruned to a perfect economy?" Is the poem complete enough to understand? Is it an enlightening poem that has rich meaning or doggerel (a term for bad poetry that does not evoke emotion)?

After reading, first determine the poem's structure. First, count the number of stanza and the number of lines in each stanza. Next, look for a regular rhyme scheme throughout the stanzas. Then count the syllables in each line and see if there is a consistent meter; if there is, analyze the feet and determine the exact type of meter. Look for repeated refrains and uses of enjambment and caesura. Finally, add all the elements together a determine the poem's specific structure:

- Free Verse: no regular rhyme scheme or meter

- Haiku: 3 lines, 17 syllables, no rhyming

- Sonnet: 14 lines, ABAB or ABBA rhyme, iambic pentmeter

- Villanelle: 19 lines, 5 stanzas, ABA rhyme scheme, repeats 1st and 3rd lines

Next, determine the conceit of the poem. The conceit is usually inferred and not stated and requires interpretation. Consider who the speaker is and who they are speaking to. Examine ideas and lines that are repeated throughout the poem. Look at what the specific structure of the poem is designed to engage: Free Verse, for example, is always about freedom or struggling for freedom, Haikus are always about nature, sonnets are always about love or heartbreak, and villanelles are always about personal loss.

Next, determine the style of the poem. What is the overall tone of the poem? What examples of imagery stick out? How does the imagery support the conceit? What interesting choices of diction are made (be specific with words)? Note: you do not discuss syntax--that is part of the structure section

Finally, critique the poem. Did the poet pick the right structure for the conceit? Is the poem stripped down to just what is needed, or as Williams calls it, "pruned to a perfect economy?" Is the poem complete enough to understand? Is it an enlightening poem that has rich meaning or doggerel (a term for bad poetry that does not evoke emotion)?

How to quote and cite a poem

When citing two or three lines of verse, treat it like a regular quotation but show line breaks separations with a / with a space on either side (// for a stanza break).

ORIGINAL TEXT: |

QUOTED IN SENTENCE: |

When you are citing four lines or more of verse, create a block quote and replicate the poem in its entirety, including any line spacing and formatting.

ORIGINAL TEXT: |

QUOTED IN ESSAY: |

As far as in-text citation, cite the name of the poet and the lines of the poem. If you have more than two poems by the same poet, cite the name of the poem in quotes as well. Cite the poem in the works cited with the poet, the name of the poem in quotes, the year of the poems first publication, and the name of the anthology (if a book, cite like a book; if a website, cite like a website).

Poems referenced

Bishop, Elisabeth. "One Art" (1976). Poetry Foundation, accessed 15 July 2018, poetryfoundation.org/poems/47536/one-art

Burn, Robert. "A Red, Red Rose" (1794). Robert Burns.com, accessed 13 June 2016, robertburns.org/works/444

cummings, e.e. "i carry your heart with me" (1952). All Poetry, accessed 13 June 2016, allpoetry.com/i-carry-your-heart-with-me

Hughes, Langston. "Harlem" (1951). Poem Hunter, accessed 13 June 2016, poemhunter.com/poem/harlem-dream-deferred

Kipling, Rudyard. "If" (1915). American Academy of Poets, accessed 13 June 2016, poets.org/poetsorg/poem/if

Plath, Sylvia. "Mad Girl's Love Song" (1951). All Poetry, accessed 13 June 2016, allpoetry.com/Mad-Girl's-Love-Song

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet (1623), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - - . "Sonnet 73" (1623). Borders Classics, 2003. p. 39.

Bishop, Elisabeth. "One Art" (1976). Poetry Foundation, accessed 15 July 2018, poetryfoundation.org/poems/47536/one-art

Burn, Robert. "A Red, Red Rose" (1794). Robert Burns.com, accessed 13 June 2016, robertburns.org/works/444

cummings, e.e. "i carry your heart with me" (1952). All Poetry, accessed 13 June 2016, allpoetry.com/i-carry-your-heart-with-me

Hughes, Langston. "Harlem" (1951). Poem Hunter, accessed 13 June 2016, poemhunter.com/poem/harlem-dream-deferred

Kipling, Rudyard. "If" (1915). American Academy of Poets, accessed 13 June 2016, poets.org/poetsorg/poem/if

Plath, Sylvia. "Mad Girl's Love Song" (1951). All Poetry, accessed 13 June 2016, allpoetry.com/Mad-Girl's-Love-Song

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet (1623), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - - . "Sonnet 73" (1623). Borders Classics, 2003. p. 39.