Drama is writing that is meant to be performed rather than read, ad is one of the five superstructures of writing (along with narrative, informational text, myth, and poetry). Drama includes plays, musical theatre, film, speeches, and, to a certain extent, lyrical music*. Drama spun out of myth; the earliest recorded dramas come from ancient Greece, where plays were religious rights depicting gods interacting with mythical heroes. However, starting with the comedies of Aristophanes, drama began to focus on modern people and problems, leaving behind its mythic roots.

Dramatic works are most connected to theatre. Theatre is any performance in front of a live audience sharing the same space as the performers. In theatre, audiences get to react to the performers in real time with their cathartic expressions (laughter, crying, gasps, shouts, etc) and performers adjust accordingly. Yet the twentieth century introduced recorded media, and now much of the drama consumed is not live in front of the audience but is recorded audio (the radio play) or recorded audio and visuals: film. Film includes everything from short TikTok sketches to seasons-long television series to three-hour cinematic movies.

While this article will focus on scripted drama (as this is a writing website), there is also unscripted drama in the modern media landscape. While usually giving edifying information, podcasts and debates require people speaking and are thus drama (which is why the text of one of these events written after the fact, called a transcript, is written in exchange format). Improvisational theatre and reality television are drama, as are most political rallies and speeches.

Dramatic works are most connected to theatre. Theatre is any performance in front of a live audience sharing the same space as the performers. In theatre, audiences get to react to the performers in real time with their cathartic expressions (laughter, crying, gasps, shouts, etc) and performers adjust accordingly. Yet the twentieth century introduced recorded media, and now much of the drama consumed is not live in front of the audience but is recorded audio (the radio play) or recorded audio and visuals: film. Film includes everything from short TikTok sketches to seasons-long television series to three-hour cinematic movies.

While this article will focus on scripted drama (as this is a writing website), there is also unscripted drama in the modern media landscape. While usually giving edifying information, podcasts and debates require people speaking and are thus drama (which is why the text of one of these events written after the fact, called a transcript, is written in exchange format). Improvisational theatre and reality television are drama, as are most political rallies and speeches.

Wrighting, Not Writing

Drama is written in exchange format, where the text is an exchange between characters and mainly consists only of lines characters say. No quotation marks are used for this dialogue, and character names are capitalized and offset by colons. Only having dialogue makes setting difficult to define, so in addition to the lines are stage directions, small descriptions in italics of where the scene takes place, actions a character takes, and the tone a character should have. The most primary of these stage directions are entrances and exits -- when actors go on and off stage. While it's helpful to read the stage directions when reading the script, stage directions are not said aloud during the actual performance.

There are two common ways of writing what characters say: dialogue and monologue. Dialogue is a set of lines shared between two or more characters and mirrors real life discussion, and monologue is where one character talks for a good deal of time like a lecture or speech. While people don't monologue often in real life, monologues are essential in drama to give characters the depth that they get through narration in stories and novels. Occasionally, dialogue between characters will be quick and rapid fire -- this style of dialogue was common in the plays of Ancient Greece and thus has a very Greek name: stichomythia.

Since scripts are meant to be performed, they are divided up into acts and scenes. An act is a large division between major changes in overall character motivation and standing. A character that may have power at the start of Act I will be powerless by Act II, and a character that faces a major obstacle in Act I will face a different sort of obstacle in Act II. Act numbers are always written in Roman numerals. Modern plays tend to have two or three acts while most plays before 1850 had five acts (like the works of Shakespeare) or one act (like Greek theatre). Acts are then divided into scenes, which occur when ither the setting is changed or most of the main characters in one scene leave and new characters enter. In Romeo and Juliet, the first and second scenes of Act II takes place in the Capulet garden, but Scene i features Mercutio talking to Benvolio and Scene ii features Romeo talking to Juliet. Scenes of older plays use lowercase Roman numerals while modern plays use regular digits.

Compared to narrative story, there is a lot missing from exchange format. Drama is intentionally left incomplete in this way and requires actors (usually under the vision of a director) to complete the story through how lines are said and how they physically interact. Since different actors can interpret a character differently than another actor, this makes each performance of drama unique and makes actors (and directors) co-creators. This is why plays are not "authored" like other works (authored is a verb meaning "composed in writing"), but are instead wrought (a verb meaning "physically crafted," like a pot or a wheel), and the person who scripts the play is called a playwright.

There are two common ways of writing what characters say: dialogue and monologue. Dialogue is a set of lines shared between two or more characters and mirrors real life discussion, and monologue is where one character talks for a good deal of time like a lecture or speech. While people don't monologue often in real life, monologues are essential in drama to give characters the depth that they get through narration in stories and novels. Occasionally, dialogue between characters will be quick and rapid fire -- this style of dialogue was common in the plays of Ancient Greece and thus has a very Greek name: stichomythia.

Since scripts are meant to be performed, they are divided up into acts and scenes. An act is a large division between major changes in overall character motivation and standing. A character that may have power at the start of Act I will be powerless by Act II, and a character that faces a major obstacle in Act I will face a different sort of obstacle in Act II. Act numbers are always written in Roman numerals. Modern plays tend to have two or three acts while most plays before 1850 had five acts (like the works of Shakespeare) or one act (like Greek theatre). Acts are then divided into scenes, which occur when ither the setting is changed or most of the main characters in one scene leave and new characters enter. In Romeo and Juliet, the first and second scenes of Act II takes place in the Capulet garden, but Scene i features Mercutio talking to Benvolio and Scene ii features Romeo talking to Juliet. Scenes of older plays use lowercase Roman numerals while modern plays use regular digits.

Compared to narrative story, there is a lot missing from exchange format. Drama is intentionally left incomplete in this way and requires actors (usually under the vision of a director) to complete the story through how lines are said and how they physically interact. Since different actors can interpret a character differently than another actor, this makes each performance of drama unique and makes actors (and directors) co-creators. This is why plays are not "authored" like other works (authored is a verb meaning "composed in writing"), but are instead wrought (a verb meaning "physically crafted," like a pot or a wheel), and the person who scripts the play is called a playwright.

Plotting Drama

Today, "drama" is colloquial for problems between people ("OMG, Sierra is such drama! I can't believe she stole Landon away from Skye!"). This actually reflects the key to dramatic writing: character tension. Unlike narrative, which focus on how situations and events effect characters, drama focuses on how character decisions effect larger stories and situations. This tension comes from characters with conflicting objectives and motivations both trying to get what they want.

Ever wonder why the book is usually very different than a film adaptation? A big part of the reason is the shift in focus from the event-focus of a narrative to the character-focus of drama. The circumstances are never as important as how the characters react to them.

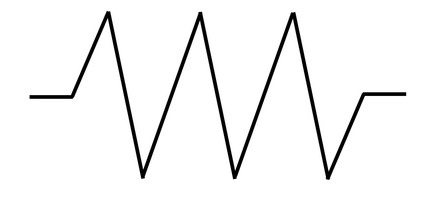

This is reflected in the plot graph for drama: it starts at stasis, a flat line representing life with no major conflict or issues. Then, characters create unrest, causing conflicts between one another. Characters bounce between great heights when they succeed and great lows when they fail, until characters finally come to settle back to stasis and contentment.

This is reflected in the plot graph for drama: it starts at stasis, a flat line representing life with no major conflict or issues. Then, characters create unrest, causing conflicts between one another. Characters bounce between great heights when they succeed and great lows when they fail, until characters finally come to settle back to stasis and contentment.

So this begs the question: how do we know when a character is content. Just like in narrative, characters build relationships, both positive and negative, based on their objective. An objective is what the character wants. At stasis, the characters are content and only want circumstances to not change. However, once a character wants something more-- a new opportunity, power, riches, freedom, love, etc.--they start creating conflict with other characters. Sometimes these characters have an opposite objective: In Hamilton, Samuel Seaberry wants others to remain loyal to Britain, while Alexander Hamilton wants to foment rebellion. Sometimes, characters fight because they have the same objective: both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr both want a key role in shaping the new nation, but they have different ideas on how to go about creating a new country.

Characters can have multiple objectives, and their objectives can change over time. Countess Aurelia in The Madwoman of Chaillot starts with an objective of wanting to help Pierre find the will to live, but then she shifts to the broader objective of saving Paris from the wealthy industrialists who want to tear her apart. Characters whose objectives and motivations change over time are called dynamic characters; characters that never change objective (like the Prospector who goes against Aurelia) are static characters.

Characters can have multiple objectives, and their objectives can change over time. Countess Aurelia in The Madwoman of Chaillot starts with an objective of wanting to help Pierre find the will to live, but then she shifts to the broader objective of saving Paris from the wealthy industrialists who want to tear her apart. Characters whose objectives and motivations change over time are called dynamic characters; characters that never change objective (like the Prospector who goes against Aurelia) are static characters.

Objectives always have motivations behind them. A motivation is the reason a character wants to achieve their objective. Sometimes characters have the same objective but different motivations: both Lysander aand Demetrius in A Midsummer Night's Dream pursue Hermia (same objective), but Demetrius is only interested in her money, while Lysander is interested in her grace and kindness (different motivations). Sometimes a character's decision is driven by two motivations: when Friar Lawrence in Romeo and Juliet gives Juliet the sleeping potion, it is not only to prevent Juliet from committing suicide out of despair, but to also prevent he marriage to Paris he is supposed to officiate (wedding a currently wed woman to another man is a sin in Lawrence's faith). Characters often question one another's motivations: in Lysistrata, the eponymous character questions Myrrhine on her commitment to the sex strike when she brings her husband into her bedroom, only to be assured when all Myrrhine does is build his frustration.

Drama is RADIAnt: rivalry, apostrophe, dramatic irony, antics

No matter what the medium or the genre, drama has four elements that help move the plot along and engage the audience: rivalry, apostrophe, dramatic irony, and antics.

RIVALRY: Rivals are two characters who come from a similar station in life, have similar traits, and seek the same objective. Since they are so similar, rivals even start out as friends and partners. However, each rival has a different motivation. Take Elphaba and Galinda's rivalry in their studies at Shiz in Wicked: Galinda is after the notoriety and popularity of studying with the Wizard, while Elphaba wants to study with the Wizard to prevent the animal abuses in Oz. Often, since rivals are after the same objective, they turn from friends to enemies. In most cases-- Elphaba and Galinda, Saliere and Mozart in Amadeus, Sweeney Todd and Judge Turpin in Sweeney Todd, Reagan and Goneril in King Lear, and so on-- one of the rivals is destroyed, literally or spiritually, by the other (though in some comedies, rivals become friends again, like Lysander and Demetrius in A Midsummer Night's Dream). Since drama is character-based and not event-based, rivalry is always a source of conflict between some if not all characters.

APOSTROPHE: In narrative, characters primarily address other characters -- if the reader needs to know something, the narrator of the story conveys it. Occasionally, they will address someone who is not physically present, such as when characters pray, write letters, or have hypothetical or imaginary conversations. This is a device called apostrophe. While not often used in literature, apostrophe is common in drama, as it allows the characters to communicate directly to the audience without use of narration. Instead of reading what a character is thinking or feeling from an outside voice, the characters in a drama directly state what they are thinking and feeling. Apostrophe is important in drama, as it lets the audience know the character's private thoughts and feelings that they don't want other characters to know. A character's speech directed to the audience and no one else is called a soliloquy while a quick expression of feelings that the audience is supposed to hear but other characters onstage are not supposed to hear is called an aside. In musicals, the songs are typically moments of apostrophe: Hamilton's "Satisfied," "Wait for It," "Hurricane," and "I Know Him" all use apostrophe to relay what characters are feeling.

RIVALRY: Rivals are two characters who come from a similar station in life, have similar traits, and seek the same objective. Since they are so similar, rivals even start out as friends and partners. However, each rival has a different motivation. Take Elphaba and Galinda's rivalry in their studies at Shiz in Wicked: Galinda is after the notoriety and popularity of studying with the Wizard, while Elphaba wants to study with the Wizard to prevent the animal abuses in Oz. Often, since rivals are after the same objective, they turn from friends to enemies. In most cases-- Elphaba and Galinda, Saliere and Mozart in Amadeus, Sweeney Todd and Judge Turpin in Sweeney Todd, Reagan and Goneril in King Lear, and so on-- one of the rivals is destroyed, literally or spiritually, by the other (though in some comedies, rivals become friends again, like Lysander and Demetrius in A Midsummer Night's Dream). Since drama is character-based and not event-based, rivalry is always a source of conflict between some if not all characters.

APOSTROPHE: In narrative, characters primarily address other characters -- if the reader needs to know something, the narrator of the story conveys it. Occasionally, they will address someone who is not physically present, such as when characters pray, write letters, or have hypothetical or imaginary conversations. This is a device called apostrophe. While not often used in literature, apostrophe is common in drama, as it allows the characters to communicate directly to the audience without use of narration. Instead of reading what a character is thinking or feeling from an outside voice, the characters in a drama directly state what they are thinking and feeling. Apostrophe is important in drama, as it lets the audience know the character's private thoughts and feelings that they don't want other characters to know. A character's speech directed to the audience and no one else is called a soliloquy while a quick expression of feelings that the audience is supposed to hear but other characters onstage are not supposed to hear is called an aside. In musicals, the songs are typically moments of apostrophe: Hamilton's "Satisfied," "Wait for It," "Hurricane," and "I Know Him" all use apostrophe to relay what characters are feeling.

DRAMATIC IRONY: Irony is the reversal of expectations from what actually happens, and dramas specialize in dramatic irony, which occurs when the audience knows information the characters don't and thus they can anticipate future events. This is not the same as foreshadowing; foreshadowing indicates something might happen, while dramatic irony indicates that something will happen. In Hamilton, we know from the first song the fate of Alexander Hamilton: that Aaron Burr is "the damn fool that shot him." In Romeo and Juliet, the prologue gives away that the two lovers die. More broadly, drama sticks to very strict story structures so audiences can anticipate when certain event, like the major setback or the inciting incident, will occur.

One common way dramas set up dramatic irony is to refer to certain items early in a play to set up the expectation that the object will be important later. As drama is constrained by a time frame, thus (the audience reasons) absolutely every line and object introduced is important and cannot be cut out. This principle is called Chekov's Gun, named for this advice by Russian playwright Anton Chekov: "If you say in the first act that there is a rifle hanging on a wall, in the second or third act it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there." In The Merchant of Venice, when Shylock makes Antonia the unusual contract requiring a pound of his flesh if he cannot pay back a loan, we know it will become a plot point later and that Antonia won't be able to pay back the loan. In Sweeney Todd, the beggar woman's repeated line "Don't I know you?" implies that she is someone from Sweeney's past, and she indeed turns out to be his long lost wife. Occasionally, this metaphorical gun is put in to mislead the audience into ignoring the actual weapon (this is called a red herring). Other times, the entire drama revolves around getting the object, even if the object or goal turns out not to be very desirable or important in the end (this is called a macguffin).

One common way dramas set up dramatic irony is to refer to certain items early in a play to set up the expectation that the object will be important later. As drama is constrained by a time frame, thus (the audience reasons) absolutely every line and object introduced is important and cannot be cut out. This principle is called Chekov's Gun, named for this advice by Russian playwright Anton Chekov: "If you say in the first act that there is a rifle hanging on a wall, in the second or third act it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there." In The Merchant of Venice, when Shylock makes Antonia the unusual contract requiring a pound of his flesh if he cannot pay back a loan, we know it will become a plot point later and that Antonia won't be able to pay back the loan. In Sweeney Todd, the beggar woman's repeated line "Don't I know you?" implies that she is someone from Sweeney's past, and she indeed turns out to be his long lost wife. Occasionally, this metaphorical gun is put in to mislead the audience into ignoring the actual weapon (this is called a red herring). Other times, the entire drama revolves around getting the object, even if the object or goal turns out not to be very desirable or important in the end (this is called a macguffin).

ANTICS: There are two definitions for antic, both of which apply to drama. The modern definition is that antics are playful and lively actions. Plays are full of high-energy antics with characters constantly moving -- they are called actors, after all. Just as a narrative writer will use a variety of long and slow paragraph constructions to create pace, drama uses a variety of sudden, quick actions and slow, weighty actions to create the pace of the dramatic work, which Aristotle in his book Poetics called rhythm. From the most delicate and slow hand movement to the most aggressive and complex dance routine, the antic nature of these actions gives the performance energy and keeps the audience engaged.

While not every action is spelled out in the stage directions, the text of the play should be read with action in mind. Some lines are longer than they would be in a narrative because an actor has to cross a stage. This information we know is repeated because it's a new act and the audience has to be reminded of what happened before the intermission break. This scene where there are no main characters exists so the actors can change costumes for their next scene.

Antic wasn't always defined by action. When first used in the 1600s, antic meant bizarre and over-the-top... something that also defines drama. Going back to Aristotle, Poetics was the first book of play analysis and Aristotle defined six elements of a drama: plot, characters, thought, language, rhythm, and spectacle. Spectacle is the idea that drama should be a little larger than life with elements that would bring an audience to see a play because it had something they hadn't seen before. In Ancient Greece, spectacle was achieved by special effects like the appeared of gods lowered by cranes onto the stage. In modern theatre, spectacle is still important, but it typically comes from the antics of the characters -- the somewhat over-the-top, bizarre, and slightly unrealistic actions that characters take.

In As You Like It, Rosalind has to dress like a man and teach the guy she likes how to woo. In A Merchant of Venice, there is a court trial (with another woman dressed as a man because Shakespeare) about cutting a pound of flesh from someone. In The Madwoman of Challiot, the titular character wears Victorian dresses and kills all the evil men in the world. The spectacle of such outlandish schemes elevate simple actions to antics. Even more grounded and realistic dramas have spectacle in the antics of characters: Oedipus blinds himself when learns of his incestuous fate, John Proctor violently shreds his confession at the end of The Crucible, and Stanley howls for his wife when he is kicked out of the house in A Streetcar Named Desire -- all of these are acts are elevated from reality and antic in nature.

While not every action is spelled out in the stage directions, the text of the play should be read with action in mind. Some lines are longer than they would be in a narrative because an actor has to cross a stage. This information we know is repeated because it's a new act and the audience has to be reminded of what happened before the intermission break. This scene where there are no main characters exists so the actors can change costumes for their next scene.

Antic wasn't always defined by action. When first used in the 1600s, antic meant bizarre and over-the-top... something that also defines drama. Going back to Aristotle, Poetics was the first book of play analysis and Aristotle defined six elements of a drama: plot, characters, thought, language, rhythm, and spectacle. Spectacle is the idea that drama should be a little larger than life with elements that would bring an audience to see a play because it had something they hadn't seen before. In Ancient Greece, spectacle was achieved by special effects like the appeared of gods lowered by cranes onto the stage. In modern theatre, spectacle is still important, but it typically comes from the antics of the characters -- the somewhat over-the-top, bizarre, and slightly unrealistic actions that characters take.

In As You Like It, Rosalind has to dress like a man and teach the guy she likes how to woo. In A Merchant of Venice, there is a court trial (with another woman dressed as a man because Shakespeare) about cutting a pound of flesh from someone. In The Madwoman of Challiot, the titular character wears Victorian dresses and kills all the evil men in the world. The spectacle of such outlandish schemes elevate simple actions to antics. Even more grounded and realistic dramas have spectacle in the antics of characters: Oedipus blinds himself when learns of his incestuous fate, John Proctor violently shreds his confession at the end of The Crucible, and Stanley howls for his wife when he is kicked out of the house in A Streetcar Named Desire -- all of these are acts are elevated from reality and antic in nature.

Analyzing a play you read

First, who are the characters? What are their motivations? How are characters and their relationships established? Who are the stock characters?

Next, describe the structure of the story. What takes the characters out of stasis? How does the story use dramatic irony? How does the play conform to genre tropes and story structure? How does it break from these conventions? What are the most memorable scenes? How do the characters return to stasis?

Look at the theme of the work. How do plot actions and character decisions support the theme?

Next, discuss style. What is the tone of the film, and how does the way each character sounds reflect this attitude? How is the script arranged: does it use a lot of apostrophe, monologues, or quick dialogue?. What is the diction of the characters like and what does it say about them? Look at the stage direction-- is there a lot of action and how is it described?

Finally, critique the medium. Why did the author choose to make a drama to tell his or her story? How is the story told differently than it would be as regular prose? Was making this story a drama an effective choice?

Next, describe the structure of the story. What takes the characters out of stasis? How does the story use dramatic irony? How does the play conform to genre tropes and story structure? How does it break from these conventions? What are the most memorable scenes? How do the characters return to stasis?

Look at the theme of the work. How do plot actions and character decisions support the theme?

Next, discuss style. What is the tone of the film, and how does the way each character sounds reflect this attitude? How is the script arranged: does it use a lot of apostrophe, monologues, or quick dialogue?. What is the diction of the characters like and what does it say about them? Look at the stage direction-- is there a lot of action and how is it described?

Finally, critique the medium. Why did the author choose to make a drama to tell his or her story? How is the story told differently than it would be as regular prose? Was making this story a drama an effective choice?

Analyzing a play performance you watch

First is still the characters and their motivations, but also describe how characters and their relationships are established visually-- through use of costuming, stature, accent, and other choices. How do the actors portray each character? Do these portrayals build chemistry (believable relationships) or do they fall flat?

Next, describe the structure of the story in the same way as if reading a play.

When analyzing the theme of the play, consider if any visuals or character decisions were made to support the theme. For example, RENT portrays the theme that true connection "in an isolated age" only comes from opening yourself up to another person. This could be supported by giving more open characters (Angel, Tom, Maureen, and Mimi) unzipped coats and more closed off characters (Roger, Mark, Joanne, and Benny) buttoned or zipped coats. This could also be supported by the lighting: the stage could have broader, diffused lighting when characters are making connections and narrow, hard lighting when they are isolated.

Next, discuss style. How does the lighting and pacing reflect and enhance the tone of the piece? As far as imagery, describe the style of set and costumes, use of color, and the way actors interact with the audience and their environment. Describe the use of sound: is there background music or do the actors sing? How does the play use blackout and scene changes to move the story along?

Finally, critique the choices of the production. Did what you saw match the themes of the script or was it bizarre? Were you able to see and hear everything? Did the play hold your interest the entire time?

Next, describe the structure of the story in the same way as if reading a play.

When analyzing the theme of the play, consider if any visuals or character decisions were made to support the theme. For example, RENT portrays the theme that true connection "in an isolated age" only comes from opening yourself up to another person. This could be supported by giving more open characters (Angel, Tom, Maureen, and Mimi) unzipped coats and more closed off characters (Roger, Mark, Joanne, and Benny) buttoned or zipped coats. This could also be supported by the lighting: the stage could have broader, diffused lighting when characters are making connections and narrow, hard lighting when they are isolated.

Next, discuss style. How does the lighting and pacing reflect and enhance the tone of the piece? As far as imagery, describe the style of set and costumes, use of color, and the way actors interact with the audience and their environment. Describe the use of sound: is there background music or do the actors sing? How does the play use blackout and scene changes to move the story along?

Finally, critique the choices of the production. Did what you saw match the themes of the script or was it bizarre? Were you able to see and hear everything? Did the play hold your interest the entire time?

How to quote and cite a play

For plays written in verse, cite lines like poetry. For all others, treat like prose. For monologues of over for lines and dialogue, use a block quote. Write character names in all caps, followed by a colon, followed by a line. If significant action happens in the selection, describe it using brackets on its own line. Remember to distinguish between a character's inner narration and dialogue.

ORLANDO: Then love me, Rosalind.

ROSALIND: Yes, faith, will I, Fridays and Saturdays, and all.

ORLANDO: And wilt thou have me?

ROSALIND: Ay, and twenty such.

ORLANDO: What sayest thou?

ROSALIND: Are you not good?

ORLANDO: I hope so. (AYL IV.i.1893-1899)

As far as in-text citation, cite the name of the drama and page UNLESS citing Shakespeare and other classic play written in verse. For these, cite the act, scene, and line numbers; furthermore, Shakespeare uses a system of play abbreviations for in-text citation if you are citing from multiple of his plays in one work. Play citations are exactly like book citations (see bottom). Live performances of plays, however, are a bit different. For these, list the playwright, name of the play in italics, director, production company name with the city and state, the date of performance, and the words "Live show."

Ex: Simon, Neil. Rumors, directed by Erin Allen. Skyline High School (Longmont, CO), 5 November 2005. Live Show.

Ex: Simon, Neil. Rumors, directed by Erin Allen. Skyline High School (Longmont, CO), 5 November 2005. Live Show.

Dramatic works discussed

Aristophanes. Lysistrata (411 BCE). Dover, 1994.

Giraudoux, Jean. The Madwoman of Chaillot (1946), adapted by Maurice Valancy. Dramatists, 1998.

Larson, Jonathan. RENT (1996). Rob Weisbach Books/William Morrow/Melcher Media, 1997.

Miller, Arthur. The Crucible (1953). Penguin Classics, 2000.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. Hamilton. Original cast recording, Atlantic Records, 2015.

Schaffer, Peter. Amadeus (1980). Harper Collins, 2001.

Schwartz, Stephen, and Winnie Holzman. Wicked (1998). Wickedly Wicked Blog, edited by Arrika, 30 January 2009, wickedlywicked.blogspot.com/2009/01/wicked-script

Sophocles. Oedipus Rex (429 BCE), translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Books, 1984.

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It (1599), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. King Lear (1605), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. The Merchant of Venice (1597), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. A Midsummer Night's Dream (1596), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet (1595), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

Sondheim, Steven, and Hugh Wheeler. Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. MTI, 1979.

Williams, Tennessee. A Streetcar Named Desire (1947. Penguin Classics, 2009.

Aristophanes. Lysistrata (411 BCE). Dover, 1994.

Giraudoux, Jean. The Madwoman of Chaillot (1946), adapted by Maurice Valancy. Dramatists, 1998.

Larson, Jonathan. RENT (1996). Rob Weisbach Books/William Morrow/Melcher Media, 1997.

Miller, Arthur. The Crucible (1953). Penguin Classics, 2000.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel. Hamilton. Original cast recording, Atlantic Records, 2015.

Schaffer, Peter. Amadeus (1980). Harper Collins, 2001.

Schwartz, Stephen, and Winnie Holzman. Wicked (1998). Wickedly Wicked Blog, edited by Arrika, 30 January 2009, wickedlywicked.blogspot.com/2009/01/wicked-script

Sophocles. Oedipus Rex (429 BCE), translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Books, 1984.

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It (1599), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. King Lear (1605), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. The Merchant of Venice (1597), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. A Midsummer Night's Dream (1596), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

- - -. The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet (1595), edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstein. Folger Shakespeare Library, 2014.

Sondheim, Steven, and Hugh Wheeler. Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. MTI, 1979.

Williams, Tennessee. A Streetcar Named Desire (1947. Penguin Classics, 2009.

*Drama is similar to poetry in that both are often performed and classical drama (like Shakespeare) often uses poetic verse. However, drama requires a storyline and characters, while poetry does not. Poetry also does not necessarily need to be performed, while drama does. Lyrical music is the only text that is both dramatic and poetic at the same time.