Beyond Truth

Mankind has told stories since the dawn of civilization. Anthropologists and biologists agree that what sets humans apart from other species is our ability to tell stories and transmit information from one generation to the next. The earliest stories humans told one another evolved as answers to their questions: Where does fire come from? Why do the seasons change? What happens when we die? These stories also celebrated the history of the tribe: the greatest warriors, the most thrilling hunt, the worst winter. These early stories became the structure known as myth. Myths are stories that seek to impart moral or cultural truths to its audience -- they are literally the stories that hold society together.

But what does this mean? Much like wild animals, primitive humans can be panicky, mistrusting, and only concerned about their own welfare. Tying people together outside of their immediate family bloodlines was difficult, so mythology was developed to bind people together. Initially, these stories were intended to teach moral precepts (murder is wrong, don't walk around alone after dark, be patient, and so on). Yet these stories bound people together with a shared sense of identity: they could talk of the same characters and stories, much how you and your friends can bond over the films and other stories you share. These stories evolved into legends of great heroes, tales to guide children, and stories of gods that became the foundation of religion -- the major truths of any culture.

"Truth? So myths are factual?" This is a fair question, as all other structures like narrative, drama, or poetry are judged on their fictive nature. Yet myths operate in a special place where they are all true and false at the same time. Confused yet? Take the mythology of the ancient Egyptians as an example-- the birth of Ra, the death and resurrection of Osiris, the judgement of souls by Anubis. No modern person would say that these stories are factually true, as there is no empirical evidence of the existence of animal-man hybrids like Ra and Anubis nor of zombie resurrections as in what happened with Osiris. Yet ancient empires believed these myths as literal truth, and even today a listener to these fantastic stories can find some deeper connection to their inner sense of truth. Thus, myth is the only structure that disregards "fictional" or "nonfictional" distinction-- it is beyond mere factuality. This is why one doesn't look for a theme in a myth but rather a moral: a universal truth that should be believed by the reader so that they may be a good person. Morals teach survival, whether it be physical survival (don't wander off into the woods), social survival (don't challenge those above you), or spiritual survival (don't make graven images).

Myths predate writing and were spread orally from person to person. As societies grew, so did the number of stories, and tribes soon had a dedicated storyteller or wise man whose sole purpose was to pass on myths. Now in a world without writing, remembering so many stories was a difficult task, yet myths have a built-in simplifier: the archetype. An archetype is a combination of the Greek stems archy (meaning "chief") and typos (meaning "model"), which serves as a perfect definition: and archetype is the chief model of an idea or concept. The most common archetype is the hero, a character who stands for moral goodness and justice even at personal cost to themselves. There are many different classic heroes (Gilgamesh, Theseus, Odysseus, Cú Chulainn) and modern heroes (Superman, Harry Potter, Luke Skywalker) who, while having different character attributes and specifics, nevertheless share common motivations and are all predictable in the same ways. Archetypes make characters easier to remember for both the storyteller and the listener, and as they are so simple, the same archetypes can be found in stories of all cultures. Archetypes are so common, in fact, that psychologist Carl Jung discovered that babies who cannot even speak can identify archetypes, leading to the idea that these ideas are innate-- that we are born with story.

But what does this mean? Much like wild animals, primitive humans can be panicky, mistrusting, and only concerned about their own welfare. Tying people together outside of their immediate family bloodlines was difficult, so mythology was developed to bind people together. Initially, these stories were intended to teach moral precepts (murder is wrong, don't walk around alone after dark, be patient, and so on). Yet these stories bound people together with a shared sense of identity: they could talk of the same characters and stories, much how you and your friends can bond over the films and other stories you share. These stories evolved into legends of great heroes, tales to guide children, and stories of gods that became the foundation of religion -- the major truths of any culture.

"Truth? So myths are factual?" This is a fair question, as all other structures like narrative, drama, or poetry are judged on their fictive nature. Yet myths operate in a special place where they are all true and false at the same time. Confused yet? Take the mythology of the ancient Egyptians as an example-- the birth of Ra, the death and resurrection of Osiris, the judgement of souls by Anubis. No modern person would say that these stories are factually true, as there is no empirical evidence of the existence of animal-man hybrids like Ra and Anubis nor of zombie resurrections as in what happened with Osiris. Yet ancient empires believed these myths as literal truth, and even today a listener to these fantastic stories can find some deeper connection to their inner sense of truth. Thus, myth is the only structure that disregards "fictional" or "nonfictional" distinction-- it is beyond mere factuality. This is why one doesn't look for a theme in a myth but rather a moral: a universal truth that should be believed by the reader so that they may be a good person. Morals teach survival, whether it be physical survival (don't wander off into the woods), social survival (don't challenge those above you), or spiritual survival (don't make graven images).

Myths predate writing and were spread orally from person to person. As societies grew, so did the number of stories, and tribes soon had a dedicated storyteller or wise man whose sole purpose was to pass on myths. Now in a world without writing, remembering so many stories was a difficult task, yet myths have a built-in simplifier: the archetype. An archetype is a combination of the Greek stems archy (meaning "chief") and typos (meaning "model"), which serves as a perfect definition: and archetype is the chief model of an idea or concept. The most common archetype is the hero, a character who stands for moral goodness and justice even at personal cost to themselves. There are many different classic heroes (Gilgamesh, Theseus, Odysseus, Cú Chulainn) and modern heroes (Superman, Harry Potter, Luke Skywalker) who, while having different character attributes and specifics, nevertheless share common motivations and are all predictable in the same ways. Archetypes make characters easier to remember for both the storyteller and the listener, and as they are so simple, the same archetypes can be found in stories of all cultures. Archetypes are so common, in fact, that psychologist Carl Jung discovered that babies who cannot even speak can identify archetypes, leading to the idea that these ideas are innate-- that we are born with story.

Caught in the Cycle

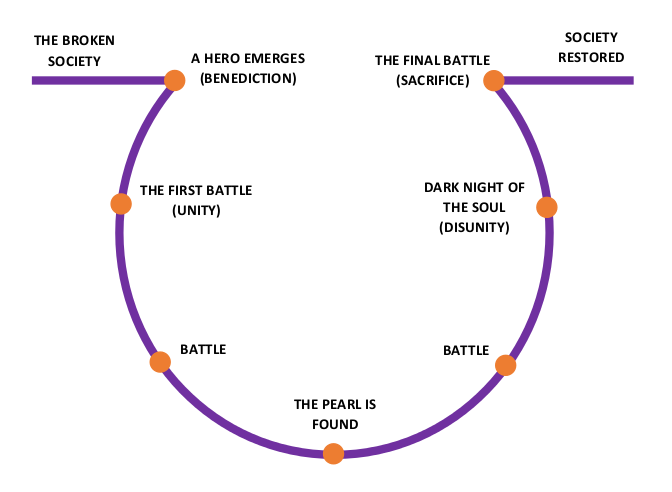

Anthropologist Joseph Campbell, a contemporary of Jung's, used stories researcher Northrop Frye collected from cultures all over the world to prove that archetypes are universal to myth-- that every hero has a thousand faces. Campbell went further and demonstrated that every myth fell into the same plot pattern, which he called the myth cycle and can be graphed on the aptly-named Campbell diagram:

- Society is broken: Some event jars everyday society into peril. This could be a major storm, the death of a king, or the rise of a monster. Only one thing can fix society: the pearl (the archetype of the ultimate prize or cure). The rest of the cycle will be an attempt to restore the broken society.

- A hero emerges: A hero is chosen, by others or by destiny, to get the pearl. Sometimes, he or she is a reluctant hero who does not want to go on the quest but is forced to. Before the hero leaves society and enters the unknown (represented by the descent on the graph), he or she receives a benediction, or a blessing by a moral authority that the hero's quest is righteous. Sometimes, this is a traditional blessing by a priest. Other times, a wealthy member of society will supply the hero with the ship or other conveyance they need for the journey. Often, the benediction comes in the form of education, with an older sage teaching the hero how to be a hero.

- First battle: The hero meets opposition for the first time and almost always loses; however, the hero is saved by a new companion. Common companions are fools, strongmen, tricksters, magicians, and maidens, and they typically go with the hero because they believe in their cause, are seeking redemption, or are pursuing their own goals. Not all companions arrive at the first battle: some start the quest with the hero, while others join during later battles.

- Subsequent battles: The next major stage is reaching the pearl-- the apex of the journey. Depending on the length and breadth of the story, there may be anywhere from zero to dozens of subsequent battles between the first battle and reaching the pearl. Often, there is at least one conflict where the hero, having lost the first battle, wins and rebuilds his or her confidence.

- The hero finds the pearl: With the companions in tow, the hero discovers the pearl. Notice that this doesn't mean the hero wins or even reaches their goal: they merely have the means to win. For example, in A New Hope, this is where Luke and company get Leia: the Death Star isn't destroyed yet, but since Leia has the plans (the pearl), the rebellion has the means to win. Here, the hero learns that reaching the pearl was only the first part of the journey, and that the villains will now be pursuing him.

- More battles: Again, depending on the length of the story, there may be more battles between the finding the pearl and reaching the dark night of the soul. One of the most common battles that occurs results in the loss of the sage character, meaning the hero must move past the learning stage and stand on their own.

- The dark night of the soul: At this point, everything is going well for the hero: they have the means to win, they've won some battles, and they are feeling confident... but this quickly ends and the hero is filled with doubt. Sometimes, the villainous forces tempt the hero to leave their journey and abandon the pearl by offering the hero wealth, power, love, or happiness; even if the hero decline, this decision will lead to a hero's self doubt. Other times, the hero arrives outside the tower (the villain's stronghold) and is suddenly betrayed by a companion pursuing their own self-interest.

- The final battle: Either to protect them or not trusting them after the betrayal, the hero leaves the companions still loyal to him to face the villain and his self-doubt alone. In this battle, the hero must overcome their doubt and remember their benediction. In order to win against the final villain, who is stronger and more experienced than the hero, the hero makes a noble sacrifice (occasionally their own life) in order to defeat the villain and repair society.

- The restoration of society: After the last battle, the companions return to the hero; often, the hero has been weakened from the battle and needs the companions to help them return to society. Society becomes whole again.

Four Flavors of Mythology

While all mythology uses archetypes and follows the myth cycle, not all myths are built for the same purpose. Traditionally, there have been three types of myths: true myths, which are religious in nature; legends, which are historical accounts; and fairy tables, which are used to teach children. When civilization developed writing, an additional form emerged: the literary myth. These four substructures are detailed below.

Matters of Faith: Aeitiological myth

A aetiological myth is story (often religious) explaining some natural or social phenomenon through gods, miracles, and magic. Well-known aetiological mythologies include Greek myths ("Narcissus and Echo," "Eros and Psyche, etc.), Norse myths ("The Death of Baulder," "Ragnorak," etc.), and Judeo-Christian Myths ("Adam and Eve," "Noah's Ark," etc.). Longer myths written in verse are called epics, which are a combination of all five literary structures (myth, narrative, edifiers, drama, and poetry) and include The Epic of Gilgamesh and Beowulf. Common topics covered by aetiological myth include the creation of the world (and the things in it), the cause of natural disasters, the reasons behind social practices and celebrations, and what comes after death. Though we commonly use “myth” as a word denoting something false, all religious truths are based on aetiological myths, and since others may believe in the truth of an aetiological myth, one must be respectful of the myth and their right to believe it.

Hidden histories: Legends and folk tales

A legend is a story that tells the unauthenticated “history” of a culture and leans more heavily on historical fact and context than religious myths. Most legends involve actual historical figures as characters and do not use magical tropes like myths and fairy tales. Legendary figures include King Arthur, Robin Hood, William Tell, and Betsy Ross. Even for figures like Arthur, where historians debate his existence, their legends all have some historical basis; for example, William Tell was an actual person who led the Swiss resistance against the Hapsburg conquest, though it's doubtful that he really shot an apple off his son's head. Sometimes, generations worth of connected legends are compiled together to serve as a complete mythical history of an area: this is known as a saga.

A key difference between true myths about heroes and legends about heroes is the presence of gods. While King Arthur receives magical help and assistance from Merlin, he does not actually encounter gods, so his tales are legendary; by the same token, while the Trojan War is proven to have occurred, The Iliad is still a true myth because it features gods. This is not to say legends are without magic objects or incredible monsters: legends are still fantastic histories. Instead of encountering gods, these legendary figures occasionally meet an avatar, which is a corporal representation of a natural force or idea. Two avatars found in legends from all over the world are the Grim Reaper, a hooded psychopomp that acts as the avatar of death, and the Green Man, a man made of plants that acts as the avatar of nature. Even stories of the Catholic saints are legendary, as the saints were actual men who existed and, while miracles feature heavily in their stories, God Himself does not feature as a character in any of them.

Some legends, especially those told in the American West, take real people and exaggerate their deeds to completely unrealistic extremes: these are tall tales and include stories of Paul Bunyan, Casey Jones, Baron Munchhausen, and Johnny Appleseed. Notice the difference between a regular legend and a tall tale: while it is unlikely that William Tell shot the apple off his son's head, it's ludicrous to believe Pecos Bill rode a tornado so well he carved the Grand Canyon. Creating tall tales continues today, as we tell tall tales about celebrities like Chuck Norris and Liam Niesson. We also still create legends that take place in the unknown shadows of modern society. These are urban legends, which are entertaining stories of uncertain origin about modern society that are circulated as though they are true. Some are a fictitious and fantastic as King Arthur, such as the Jersey Devil or Mothman; others have a specific factual basis like William Tell, such as the Virginia Bunnyman and "The Hairy-Armed Hitchhiker."

A key difference between true myths about heroes and legends about heroes is the presence of gods. While King Arthur receives magical help and assistance from Merlin, he does not actually encounter gods, so his tales are legendary; by the same token, while the Trojan War is proven to have occurred, The Iliad is still a true myth because it features gods. This is not to say legends are without magic objects or incredible monsters: legends are still fantastic histories. Instead of encountering gods, these legendary figures occasionally meet an avatar, which is a corporal representation of a natural force or idea. Two avatars found in legends from all over the world are the Grim Reaper, a hooded psychopomp that acts as the avatar of death, and the Green Man, a man made of plants that acts as the avatar of nature. Even stories of the Catholic saints are legendary, as the saints were actual men who existed and, while miracles feature heavily in their stories, God Himself does not feature as a character in any of them.

Some legends, especially those told in the American West, take real people and exaggerate their deeds to completely unrealistic extremes: these are tall tales and include stories of Paul Bunyan, Casey Jones, Baron Munchhausen, and Johnny Appleseed. Notice the difference between a regular legend and a tall tale: while it is unlikely that William Tell shot the apple off his son's head, it's ludicrous to believe Pecos Bill rode a tornado so well he carved the Grand Canyon. Creating tall tales continues today, as we tell tall tales about celebrities like Chuck Norris and Liam Niesson. We also still create legends that take place in the unknown shadows of modern society. These are urban legends, which are entertaining stories of uncertain origin about modern society that are circulated as though they are true. Some are a fictitious and fantastic as King Arthur, such as the Jersey Devil or Mothman; others have a specific factual basis like William Tell, such as the Virginia Bunnyman and "The Hairy-Armed Hitchhiker."

Magical morals: Folklore and fairy tales

While true myths and legends straddle the line between truth and fiction, they are held as lore, or a body of ancient knowledge treated as true by most members of a culture. Yet folklore is different. While both lore and folklore are primarily passed on by word of mouth, folklore consists of stories that are obviously fictional but still convey a moral truth or lesson. One of the most common types of folklore are fables, which are very short stories (usually less than 300 words) with talking animals and the occasional human as the main characters. There is typically no magic in fables outside the idea that animals can talk, and these animals are typically given archetypal traits (foxes are clever, lions are regal, wolves are brutal killing machines). The most famous fables are those by Aesop, which include "The Boy Who Cried Wolf" and "The Tortoise and the Hare." Modern fables are a bit longer, and include the Br'er Rabbit stories of the American South and the Ananzi stories of Africa.

Fairy tales are also fairly well known in a culture. A fairy tale is a short story featuring children and adolescents dealing with magical circumstances in order to grow up. Fairy tales may also have talking animals, but they use mostly human characters and, unlike fables, are longer and more reliant on imaginary beings and lands. Fairy tales often use orphaned characters, a repeated motif of the number three, and feature both high class kings and princess and lower class yeomen and merchants. Some popular fairy tales include the Germanic tales collected by the Brothers Grimm and the Scandinavian tales collected by Hans Christian Andersen. A third type of folklore is the parable, which is an intentionally fictional story used by religious teachers or prophets to teach a point about faith. While these speak to religious matters, their authors admit that parables are fictional allegories; thus, they are not true myth. Some examples of parables include the "Parable of the Prodigal Son" in Christianity, The Sufi in Islam, and The Adventures of Rabbi Harvey in Judaism.

Fairy tales are also fairly well known in a culture. A fairy tale is a short story featuring children and adolescents dealing with magical circumstances in order to grow up. Fairy tales may also have talking animals, but they use mostly human characters and, unlike fables, are longer and more reliant on imaginary beings and lands. Fairy tales often use orphaned characters, a repeated motif of the number three, and feature both high class kings and princess and lower class yeomen and merchants. Some popular fairy tales include the Germanic tales collected by the Brothers Grimm and the Scandinavian tales collected by Hans Christian Andersen. A third type of folklore is the parable, which is an intentionally fictional story used by religious teachers or prophets to teach a point about faith. While these speak to religious matters, their authors admit that parables are fictional allegories; thus, they are not true myth. Some examples of parables include the "Parable of the Prodigal Son" in Christianity, The Sufi in Islam, and The Adventures of Rabbi Harvey in Judaism.

By the book: Literary tales

Finally, as myths are one of the five writing structures, some authors intentionally write fictional pieces with mythic elements and archetypes. These are literary tales, stories that comes from a play or novel but are treated like a myth, legend, or fairy tale over time by society. A great example is the story of Frankenstein: while Frankenstein was written by Mary Shelley in 1818, the doctor and creature from the book have reached mythic status. There are so many films, cartoons, costumes, and stories involving Frankenstein's monster that most people encounter the creature in a form of media not directly tied to the original novel (the monster's green skin, his flat head, and Frankenstein's assistant Ygor, for instance, all come from James Whale's 1931 film and are absent from Shelley's book). Eventually, over centuries, the original work will be forgotten and only the oral tradition will remain. Atlantis is another example: it was originally a rhetorical example from the writings of Plato but is now thought to be a real "lost continent." Similar literary tales include The Three Musketeers, Alice in Wonderland, Sherlock Holmes, Peter Pan, The Wizard of Oz, Dracula, and Don Quixote.