False Claims (Logos)

Accumulatio. The emphasis or summary of previously made points or inferences by excessive praise or accusation.

Acutezza. Wit or wordplay used in rhetoric.

Aetiologia. Giving a cause or a reason.

Alloisis. The breaking down of a subject into its alternatives.

Amplification. The act and the means of extending thoughts or statements to increase rhetorical effect, to add importance, or to make the most of a thought or circumstance.

Anacoenosis. A speaker asks his or her audience or opponents for their opinion or answer to the point in question.

Anecdote. A brief narrative describing an interesting or amusing event.

Antinome Two ideas about the same topic that can be worked out to a logical conclusion, but the conclusions contradict each other.

Antonomasia. The substitution of an epithet for a proper name.

Apophasis / Apophesis. Pretending to deny something as a means of implicitly affirming it. As paralipsis, mentioning something by saying that you will not mention it. The opposite of occupatio.

Aporia. An attempt to discredit an opposing viewpoint by casting doubt on it.

Aureation. The use of Latinate and polysyllabic terms to "heighten" diction.

Auxesis. To place words or phrases in a certain order for climactic effect.

Axioms. The point where scientific reasoning starts. Principles that are not questioned.

Bases. The issues at question in a judicial case.

Bathos. An emotional appeal that inadvertently evokes laughter or ridicule.

Bdelygmia. Expression of hatred or contempt.

Bomphiologia. Bombastic speech: a rhetorical technique wherein the speaker brags excessively.

Burden of proof. Theory of argument giving the obligation of proving a case to the asserting party.

Buzzword. A word or phrase used to impress, or one that is fashionable.

Charisma. An attribute that allows a speaker's words to become powerful.

Constraints. Referring to "persons, events, objects, and relations that are parts of the situation because they have the power to constrain decision and action needed to modify the exigence". Originally used by Lloyd Bitzer.

Contingency. In rhetoric, it relates to the contextual circumstances that do not allow an issue to be settled with complete certainty.

Conversation model. The model, in critique of traditional rhetoric by Sally Gearhart, that maintains the goal of rhetoric is to persuade others to accept your own personal view as correct.

Cookery. Plato believed rhetoric was to truth as cookery was to medicine. Cookery disguises itself as medicine and appears to be more pleasing, when in actuality it has no real benefit.

Concession. Acknowledgment of objections to a proposal.

Deduction. Moving from an overall hypothesis to infer something specific about that hypothesis.

Diallage. Establishing a single point with the use of several arguments.

Dissoi logoi. Contradictory arguments.

Dysphemism. A term with negative associations for something in reality fairly innocuous or inoffensive.

Enthymeme. A type of argument that is grounded in assumed commonalities between a rhetor and the audience. (For example: Claim 1: Bob is a person. Therefore, Claim 3: Bob is mortal. The assumption (unstated Claim 2) is that People are mortal). In Aristotelian rhetoric, an enthymeme is known as a "rhetorical syllogism:" it mirrors the form of a syllogism, but it is based on opinion rather than fact (For example: Claim 1: These clothes are tacky. Claim 2: I am wearing these clothes. Claim 3: Therefore, I am unfashionable).

Enumeratio. Making a point more forcibly by listing detailed causes or effects; to enumerate: count off or list one by one.

Epizeuxis. Emphasizing an idea using one word repetition.

Eristic. Communicating with the aim of winning the argument regardless of truth. The idea is not necessarily to lie, but to present the communication so cleverly that the audience is persuaded by the power of the presentation.

Erotema. The so-called 'Rhetorical Question', where a question is asked to which an answer is not expected.

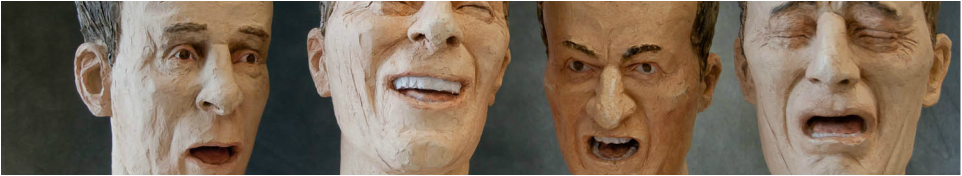

Ethopoeia. The act of putting oneself into the character of another to convey that persons feelings and thoughts more vividly.

Exigence. A rhetorical call to action; a situation that compels someone to speak out.

Hyperbaton. A figure of speech in which words that naturally belong together are separated from each other for emphasis or effect.

Hypophora. When a speaker asks aloud what his/her adversaries have to say for themselves or against the speaker, and then proceeds to answer the question. For example (from Rhetorica ad Herennium), "When he reminded you of your old friendship, were you moved? No, you killed him nevertheless, and with even greater eagerness. And then when his children grovelled at your feet, were you moved to pity? No, in your extreme cruelty you even prevented their father's burial."

Hysteron proteron. A rhetorical device in which the first key word of the idea refers to something that happens temporally later than the second key word. The goal is to call attention to the more important idea by placing it first.

Ignoratio elenchi. A conclusion that is irrelevant.

Indignatio. To arouse indignation in the audience.

Ioci. Jokes, see: Cicero's De Oratore and his theory of humor.

Irony. A deliberate contrast between indirect and direct meaning to draw attention to the opposite.

Isocolon. A string of phrases of corresponding structure and equal length.

Koinoi topoi. Common topics; in a rhetoric situation, useful arguments and strategies.

Koinonia. To consult with your opponent or judge.

Kolakeia. Flattery; telling people what they want to hear while disregarding their best interests; employed by sophistic rhetoricians.

Major premise. Statement in a syllogism. Generalization.

Material fallacy. False notion concerning the subject matter of an argument.

Minor premise. Statement in an argument.

Motive. Something that plays a role in one's decision to act.

Necessary cause. Cause without which effect couldn't/wouldn't have occurred.

Noema. Speech that is deliberately subtle or obscure.

Occupatio. Introducing and responding to one's opponents' arguments before they have the opportunity to bring them up. The opposite of apophasis.

Oictos. A show of pity or compassion.

Paradeigma. Greek, argument created by a list of examples that leads to a probable generalized idea.

Paradiastole. Greek, redescription - usually in a better light.

Paralipsis. A form of apophasis when a rhetor introduces a subject by denying it should be discussed. To

Periphrasis. The substitution of many or several words where one would suffice; usually to avoid using that particular word.

Plausibility. Rhetoric that is believable right away due to its association with something that the audience already knows or has experienced.

Portrayal. Describing a person clearly enough for recognition. For example (from Rhetorica ad Herennium), "I mean him, men of the jury, the ruddy, short, bent man, with white and rather curly hair, blue-grey eyes, and a huge scar on his chin, if perhaps you can recall him to memory."

Pragmatographia. Description of an action (such as a battle, a feast, a marriage, a burial, etc.).

Prolepsis. A literary device in which a future state is spoken of in the present; for example, a condemned man may be called a "dead man walking".

Reasoning by contraries. Where the first statement of two opposite statements directly proves the second. For example (from Rhetorica ad Herennium), "Or how should you expect a person whose arrogance has been insufferable in private life, to be agreeable and not forget himself when in power...?"

Rhetorical question. A question asked to make a point instead of to elicit a direct answer.

Sententia. Applying a general truth to a situation by quoting a maxim or other wise saying as a conclusion or summary of that situation.

Syllogism. A type of valid argument that states if the first two claims are true, then the conclusion is true. (For example: Claim 1: People are mortal. Claim 2: Bob is a person. Therefore, Claim 3: Bob is mortal.) Started by Aristotle.

Tautologia. The same idea repeated in different words.

Acutezza. Wit or wordplay used in rhetoric.

Aetiologia. Giving a cause or a reason.

Alloisis. The breaking down of a subject into its alternatives.

Amplification. The act and the means of extending thoughts or statements to increase rhetorical effect, to add importance, or to make the most of a thought or circumstance.

Anacoenosis. A speaker asks his or her audience or opponents for their opinion or answer to the point in question.

Anecdote. A brief narrative describing an interesting or amusing event.

Antinome Two ideas about the same topic that can be worked out to a logical conclusion, but the conclusions contradict each other.

Antonomasia. The substitution of an epithet for a proper name.

Apophasis / Apophesis. Pretending to deny something as a means of implicitly affirming it. As paralipsis, mentioning something by saying that you will not mention it. The opposite of occupatio.

Aporia. An attempt to discredit an opposing viewpoint by casting doubt on it.

Aureation. The use of Latinate and polysyllabic terms to "heighten" diction.

Auxesis. To place words or phrases in a certain order for climactic effect.

Axioms. The point where scientific reasoning starts. Principles that are not questioned.

Bases. The issues at question in a judicial case.

Bathos. An emotional appeal that inadvertently evokes laughter or ridicule.

Bdelygmia. Expression of hatred or contempt.

Bomphiologia. Bombastic speech: a rhetorical technique wherein the speaker brags excessively.

Burden of proof. Theory of argument giving the obligation of proving a case to the asserting party.

Buzzword. A word or phrase used to impress, or one that is fashionable.

Charisma. An attribute that allows a speaker's words to become powerful.

Constraints. Referring to "persons, events, objects, and relations that are parts of the situation because they have the power to constrain decision and action needed to modify the exigence". Originally used by Lloyd Bitzer.

Contingency. In rhetoric, it relates to the contextual circumstances that do not allow an issue to be settled with complete certainty.

Conversation model. The model, in critique of traditional rhetoric by Sally Gearhart, that maintains the goal of rhetoric is to persuade others to accept your own personal view as correct.

Cookery. Plato believed rhetoric was to truth as cookery was to medicine. Cookery disguises itself as medicine and appears to be more pleasing, when in actuality it has no real benefit.

Concession. Acknowledgment of objections to a proposal.

Deduction. Moving from an overall hypothesis to infer something specific about that hypothesis.

Diallage. Establishing a single point with the use of several arguments.

Dissoi logoi. Contradictory arguments.

Dysphemism. A term with negative associations for something in reality fairly innocuous or inoffensive.

Enthymeme. A type of argument that is grounded in assumed commonalities between a rhetor and the audience. (For example: Claim 1: Bob is a person. Therefore, Claim 3: Bob is mortal. The assumption (unstated Claim 2) is that People are mortal). In Aristotelian rhetoric, an enthymeme is known as a "rhetorical syllogism:" it mirrors the form of a syllogism, but it is based on opinion rather than fact (For example: Claim 1: These clothes are tacky. Claim 2: I am wearing these clothes. Claim 3: Therefore, I am unfashionable).

Enumeratio. Making a point more forcibly by listing detailed causes or effects; to enumerate: count off or list one by one.

Epizeuxis. Emphasizing an idea using one word repetition.

Eristic. Communicating with the aim of winning the argument regardless of truth. The idea is not necessarily to lie, but to present the communication so cleverly that the audience is persuaded by the power of the presentation.

Erotema. The so-called 'Rhetorical Question', where a question is asked to which an answer is not expected.

Ethopoeia. The act of putting oneself into the character of another to convey that persons feelings and thoughts more vividly.

Exigence. A rhetorical call to action; a situation that compels someone to speak out.

Hyperbaton. A figure of speech in which words that naturally belong together are separated from each other for emphasis or effect.

Hypophora. When a speaker asks aloud what his/her adversaries have to say for themselves or against the speaker, and then proceeds to answer the question. For example (from Rhetorica ad Herennium), "When he reminded you of your old friendship, were you moved? No, you killed him nevertheless, and with even greater eagerness. And then when his children grovelled at your feet, were you moved to pity? No, in your extreme cruelty you even prevented their father's burial."

Hysteron proteron. A rhetorical device in which the first key word of the idea refers to something that happens temporally later than the second key word. The goal is to call attention to the more important idea by placing it first.

Ignoratio elenchi. A conclusion that is irrelevant.

Indignatio. To arouse indignation in the audience.

Ioci. Jokes, see: Cicero's De Oratore and his theory of humor.

Irony. A deliberate contrast between indirect and direct meaning to draw attention to the opposite.

Isocolon. A string of phrases of corresponding structure and equal length.

Koinoi topoi. Common topics; in a rhetoric situation, useful arguments and strategies.

Koinonia. To consult with your opponent or judge.

Kolakeia. Flattery; telling people what they want to hear while disregarding their best interests; employed by sophistic rhetoricians.

Major premise. Statement in a syllogism. Generalization.

Material fallacy. False notion concerning the subject matter of an argument.

Minor premise. Statement in an argument.

Motive. Something that plays a role in one's decision to act.

Necessary cause. Cause without which effect couldn't/wouldn't have occurred.

Noema. Speech that is deliberately subtle or obscure.

Occupatio. Introducing and responding to one's opponents' arguments before they have the opportunity to bring them up. The opposite of apophasis.

Oictos. A show of pity or compassion.

Paradeigma. Greek, argument created by a list of examples that leads to a probable generalized idea.

Paradiastole. Greek, redescription - usually in a better light.

Paralipsis. A form of apophasis when a rhetor introduces a subject by denying it should be discussed. To

Periphrasis. The substitution of many or several words where one would suffice; usually to avoid using that particular word.

Plausibility. Rhetoric that is believable right away due to its association with something that the audience already knows or has experienced.

Portrayal. Describing a person clearly enough for recognition. For example (from Rhetorica ad Herennium), "I mean him, men of the jury, the ruddy, short, bent man, with white and rather curly hair, blue-grey eyes, and a huge scar on his chin, if perhaps you can recall him to memory."

Pragmatographia. Description of an action (such as a battle, a feast, a marriage, a burial, etc.).

Prolepsis. A literary device in which a future state is spoken of in the present; for example, a condemned man may be called a "dead man walking".

Reasoning by contraries. Where the first statement of two opposite statements directly proves the second. For example (from Rhetorica ad Herennium), "Or how should you expect a person whose arrogance has been insufferable in private life, to be agreeable and not forget himself when in power...?"

Rhetorical question. A question asked to make a point instead of to elicit a direct answer.

Sententia. Applying a general truth to a situation by quoting a maxim or other wise saying as a conclusion or summary of that situation.

Syllogism. A type of valid argument that states if the first two claims are true, then the conclusion is true. (For example: Claim 1: People are mortal. Claim 2: Bob is a person. Therefore, Claim 3: Bob is mortal.) Started by Aristotle.

Tautologia. The same idea repeated in different words.

COMPOSITIONAL FALLACY: The compositional fallacy applies to characterization of stakeholders. The additional compositional fallacy assumes that characteristics or beliefs of some of a group applies to the entire group: Recent terrorist attacks have been carried out by radical Islamic groups, therefore all terrorists are Muslims. The divisional compositional fallacy assumes that characteristics or beliefs of a group automatically apply to any individual member: Most Conservatives wish to ban gay marriage, therefore all conservatives are homophobic.

IGNORANCE FALLACY: The ignorance fallacy holds that a claim is true simply because it has not been proven false (or false because it has not been proven true). Nobody has found proof that God exists, so there is no God and nobody has found proof of aliens, so aliens must not exist are common arguments. These claims dismiss the entire argument, as they do not entertain the possibility of proof, yet are extremely weak: should any proof be unearthed, this argument is destroyed

INCREDULITY FALLACY: The incredulity fallacy holds that a claim sounds unbelievable, it must not be true. For example is the statement, The eye is an incredibly complex biomechanical machine-- how could that exist without an intelligent designer? Not only does this ignore the millions of years of evolution that went into the eye development and the flaws of the human eye (only three color rods, no night vision), but by starting from a position that any proof will not be believed. Related to this is the Relativist Fallacy, which rejects a claim thinking that truth is relative to a person or group: Statistics may say crime is going down, but I still fear more unsafe than ever. Truth is objective, which is why this is a fallacy.

PROBABILITY FALLACY: The opposite of the incredulity fallacy, the probability fallacy assumes that since something could happen, it will inevitably happen. There are billions of galaxies in the universe, so there must be another planet with intelligent life on it. This ignores the reality of physical, geographical, historical, and logical limitations. Not everything is possible: I will not wake up tomorrow on a raft in the middle of the Indian Ocean with Abraham Lincoln wearing a bikini. This is related to the Gambler's Fallacy, which assumes that past outcomes will affect future outcomes (I've flipped this coin 10 times in a row and it's been heads; therefore, the next coin flip will be tails.)

SIN OF THE MASSES: A sin of the masses tries to excuse a problem or issue as irrelevant because the behavior was commonly practiced. This bank has some problems with corruption, but there's nothing going on that doesn't go on in all the other banks. or Sure, Thomas Jefferson owned slaves, but almost everyone owned slaves back then, so it's not a big deal. The wrongdoing of others does not justify the wrongdoing of an individual case, no matter how widespread the behavior is.

VALUE FALLACY (BANDWAGONS): The value fallacy refers to a claim that something is better because of its value. Value could be monetary value: This phone costs more, so it must be better. Value could be novelty: New Coke is going to be so much better than Coke because it's new. Value can be aesthetic: Macs are prettier than PCs, so they must work better. Value can also be cultural value: Everyone says milk is good for your bones, so it must be true. This last example is called a bandwagon, which is a claim that something is true because most people believe it, support it, or are doing it.

Bad Evidence (Logos: Data)

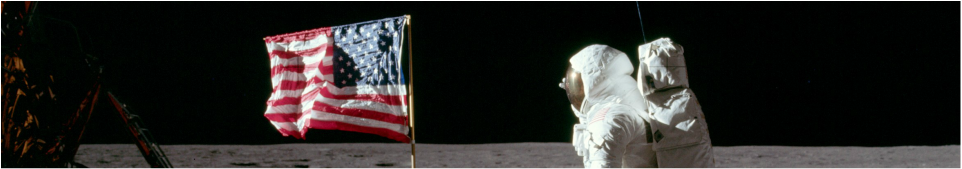

AD HOC: An ad hoc argument tries to defend an opinion that is obviously wrong by manipulating data. There are Bad Ad Hoc Festivals that celebrate such bad arguments, with topics that have included Baby human physiology developed so children could be dropkicked, Squirrels bury acorns because they resemble severed squirrel heads, and Humans sleep to keep from shrinking. Ad hoc arguments survive through the use of Confirmation Bias, which is cherry-picking evidence that supports your idea while ignoring contradicting evidence. The moon landing was faked-- the photographs are fake, the video was staged, all moon rocks are props, rockets can blast off but cannot leave the atmosphere... Ad hoc arguments also survive by suppressing evidence, where the author intentionally fails to use significant and relevant information that counts against one’s own conclusion. This is occasionally called the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy.

ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE ONLY: An anecdote is a short story told by the speaker that illustrates the main points of the story. Anecdotes are a great way to break down a topic to a personal level and engender pathos. However, anecdotes cannot be the only evidence provided: My grandfather smoked 40 a day and he lived until he was 90! is not proof that smoking is not harmful; all populations have statistical exceptions.

BLACK OR WHITE: A black or white false dilemma presents an either-or situation as the only two options while hiding alternatives. We're going to have to cut the state's education budget or go deeper into debt. In this example, there are multiple ways to prevent education cuts and more dept: the state could cut another department, borrow money, or raise taxes.

BURDENLESS PROOF: The idea of burden of proof requires each side of an argument to prove why their case is true. An argument of burdenless proof says the opposite-- "I don't need to prove my claim is true: you must prove it is false." This is not allowed in proper rhetoric

LIE: A lie is an outright untruth repeated knowingly as a fact.

NO COUNTER CLAIMS: A non-counterable or unfalsafiable claim cannot be proven false because there is no way to check if it is false or not. He lied because he’s possessed by demons. The opposition can't do anything with that claim, and these statements end conversation.

NO TRUE SCOTSMAN: When an author claims that a group of ideas share a similar quality and an exception is presented, the no true Scotsman tactic excludes the exception as not a "true" example. All true films are shot on traditional cameras. It doesn't matter that Tangerine was screened at Sundance, came out on DVD, and is on the "Best of 2015" film lists-- it was shot on an iPhone, so it's not a real film. This fallacy makes assumptions of how things are categorized and rejects any attempt at challenging the categorization.

PERFECTIONISM: Perfectionism rejects anything that will not work perfectly. What's the point of this anti-drunk driving campaign? People are still going to drink and drive no matter what. Perfection assumes that all solutions are all or nothing, which is not accurate to real life.

RED HERRING: A red herring introduces irrelevant material to the argument to distract and lead toward a different conclusion. Red herrings are beloved and welcome in mystery stories, but are despised in rhetoric. The Senator needn’t account for irregularities in his expenses when the debt limit keeps going up. Red herrings distract from the main argument in the same way as a non sequitur distracts in a narrative.

SWEEPING GENERALIZATION: A sweeping generalization comes from applying an idea too broadly and can come about in a couple of ways. One is spotlighting: to spotlight data is to assuming an observation from a small sample size applies to an entire group: Apple employs Chinese sweatshop labor, so use of sweatshops must be a huge problem in the industry. Biased generalizing occurs when a writer uses an unrepresentative sample to increase the strength of the argument: Our website poll found that 90% of internet users oppose online piracy laws. This can also happen with ideas: the undistributed middle assumes because two things share a property, that makes them the same thing: A theory can mean an unproven idea, and scientists use the term evolutionary theory, so evolution is an unproven idea.

TWO WRONGS AS RIGHT: If your thesis has a significant issue, it is not dismissed because the opposition also has an issue. Yes,torture is inhumane, but it's okay to torture terrorist because they are criminals!” One wrong does not cancel out another. Two wrongs don't make a right.

Faulty Reasoning and Conclusions (Logos: Warrant)

AFFIRMING THE CONSEQUENT: To affirm the consequent is to assume there's only one explanation for an observation when there could be many. Marriage often results in the birth of children, so that's the reason why it exists. This ignores the other benefits of marriage, such as pooling financial resources and providing love and companion. It also ignores a significant population that get married when they can't have children because they are too old or infertile or same-sex.

CIRCULAR LOGIC: A conclusion that is derived on the conclusion is called circular logic.“The key to success is the best employees. We know the employees are the best because they make the company successful.” A version of this is begging the question, where a claim is made on a premise that itself requires proof: Everyone wants to buy their kid a Turboman doll because it's the hottest toy of the season.

JUMPING TO CONCLUSIONS: When jumping to conclusion, an author draws a quick conclusion without fairly considering relevant (and easily available) evidence. She wants the birth control pill in her medical coverage? What a tramp! This conclusion presumes that the woman wants birth control so she can sleep with lots of men without consequence; however, many women use the pill to regulate their hormones or for family planning after already having children with a single partner.

MIDDLE GROUND: Assuming that because two opposing arguments have merit, the answer must lie somewhere between them is the middle ground fallacy. This usually comes as a result of two opposing opinions, but not opposing facts. I rear ended your car but I don't think I should pay for the damage. You think I should pay for all the damage. A fair compromise would be to split the bill in half. While compromise is admirable, it is not always the most just solution.

POST HOC ERGO PROPTER HOC: This common fallacy is where an author claims that because one event followed another, it was also caused by it. Since the election of the President more people than ever are unemployed. This ignores the fact that correlation (that two things happen at the same time) is not the same as causation. This sometimes ignores a common cause (We had the sexual revolution; now people die of AIDS) or denying an antecedent event (If you don’t get a degree, you won’t get a good job). A related fallacy is Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, which is a claim two events that occur simultaneously (not one after another) must be related: School shooting became more widespread when first-person shooter games became popular with teenage boys; therefore, shooter games cause violent behavior.

SLIPPERY SLOPE: A slippery slope assumes a relatively small first step will inevitably lead to a chain of related (negative) events. If we legalize gay marriage, then we'll have to recognize all sorts of marriages, like marriages with multiple partners and marriages between adult and children and marriages between people and animals, and that'll be the end of marriage.” Each of these examples has nothing to do with gay marriage, have more legal barriers, and do not have the same degree of social acceptance.

Ethical Fallacies (Ethos)

AD HOMINEM: Ad hominem is as error in logos. Instead of attacking an argument, the writer attacks the person who said the argument instead. Anyone that says we should let Muslim immigrants into our country is an American-hating liberal. Note that ad hominum does still apply to elections when actual people are the arguments. While one candidate for president can criticize the voting record or comments of another candidate, attacks on aspects of their lives like their family life and religion are considered off limits as they have nothing to do with the job of being president. Related to this is circumstance ad hominem, where an opponent states a claim isn’t credible only because of the advocate’s interests in their claim: An oil company's study on the health risks of fracking surely can't be trustworthy.

GUILT BY ASSOCIATION: To claim guilt by association is to discredit an idea or claim by associating it with an undesirable person or group. Relaxing the anti-terrorism laws is just what the terrorists want us to do. Are you saying you support terrorism? Making claims of guilt by association ignores other legitimate reasons to support a certain idea.

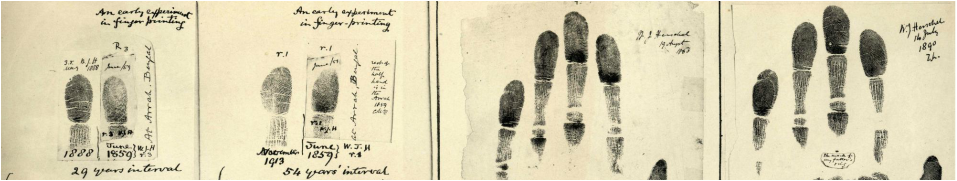

MOVING THE GOALPOST: Moving the goalpost refers to a writer's continual denial of evidence as "not being enough" to prove or disprove a point. A famous example can be seen in evolution deniers who argue that man and apes did not evolve from a common ancestor (homo nadeli) because there is a "missing link" in the fossil record-- a transitory fossil between homo sapiens (us) and homo nadeli. In 1974, Mary Leaky found such a transitional fossil in Tanzania: Australopithecus afarensis. Instead of accepting the evidence, evolution deniers instead moved the goalpost and claimed that no transitional fossil exists between Australopithecus afarensis and homo sapians. As the burden of proof is always increasing, there is no way to win the argument.

STRAWMAN: A strawman is an error in ethos where the counterargument is convoluted into something less complex so it is easier to defeat. Take the argument to allow teachers to be armed in schools. An advocate could paint the argument as, "You don't think teachers to be armed? So you are okay with putting our kids in danger?" There are lots of good reasons to not arm teachers-- issues with purchasing and training, the ethics of offensive versus defensive tactics, the potential frequency of accidental discharge, issues of security of weapons in a classroom, that police can't differentiate teachers from active shooters in an emergency-- but the strawman ignores all this and makes the issue only about child safety.

Emotional Fallacies (Pathos)

BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE: Typically called sex appeal, the beautiful people fallacy is used mostly in advertising. By depicting a beautiful and popular person using a product, the message is that you can be beautiful and popular if you use the product too. This fallacy also covers ads where the goal is to not be beautiful, but to get a guy or a girl who is beautiful by using the product.

FEAR BAITING: Fear baiting is where an argument is made by increasing fear and prejudice toward the opposing side. Before you know it there will be more mosques than churches. While fear can be used as part as pathos (I fear that if we do not act soon, the changes will be irreversible), fear baiting uses irrational and unsubstantiated fears. In this example, an increase of Islamic worship would not at all affect the practice of Christianity. A common method of fear baiting is misleading vividness, where an author describes a rare occurrence in vivid detail to convince someone that it is a widespread problem: After a court decision to legalize gay marriage, school libraries were required to stock same-sex literature and primary schoolchildren were given homosexual fairy tales.

FLATTERY: Flattery is using an irrelevant compliment to slip in an unfounded claim, which is accepted along with the compliment. Intelligent people, like the people at this rally, can clearly see that my opponent has rigged the system.

PITY PARTY: A pity party is an attempt to induce pity to sway opponents. Yes, he was an SS member, but he's is an old, dying man; it's wrong to make him stand trial for Holocaust atrocities at his age. Personal affectations and judgments should not weigh into ethical matters.

RIDICULE: Ridicule is presenting the opponent's argument in a way that makes it appear absurd. Faith in God is like believing in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy. While this may inspire laughter from supporters, those who are undecided or against the arguments will suddenly leave it, as this is putting on airs and demeaning part of the audience. This also applies to spiteful claims that are less about inspiring joy and more about inspiring anger: Don't you just hate how those rich Liberal Hollywood actors go on TV to promote their agendas?

WISHFUL THINKING: Wishful thinking is suggesting a claim is true or false just because you strongly hope it is, not because the evidence concludes it is. The President wouldn’t lie: he’s our leader and a good American, and I don't believe he could lie to the American people. This is often used with ad hoc evidence.