BOUND BY OUR BODIES

Affliction theory falls into the category of SOCIETAL MIRRORS, or criticisms that reflect society (social mirrors also include Marxism, feminism, queer theory, ecocriticism, and postcolonialism). Societal mirrors focus on the idea of The Other, a term for a person in society with little power or agency (the ability to change their circumstances). Those with agency are known as the privileged group, as they have access to resources that The Other does not. Some members of the privileged group actively work toward this inequality, while most members of the privileged group have social blindness--they do not willfully wish to subjugate others, but because their privilege is normal, they do not perceive or understand the struggles of The Other. Affliction theory focuses on the lack of agency of characters afflicted with something that makes their physical body different than the others in the story.

Wait... isn't everyone's body different?

This is the central truth of affliction theory: nobody's perfect (well, almost nobody--we'll get there). Some people have noses that are very long or very short, some have huge feet, some have moles or freckles, and that's just the start of millions of imperfections a single person has. But wait--who says that these are imperfections? According to leading affliction theorist Rosemarie Garland-Thompson, every society creates what the ideal man and woman look like--for current American culture, this is the Adonis figure with his broad chest, muscular arms, chiseled abs, and (as of this moment) rough stubble that isn't a bare cheek and isn't a full beard. Note that this ideal body, which Garland-Thompson calls the normate, is culturally constructed and can change at any time; in the recent past, mustachioed, clean-shaven, and full-bearded men have been the normate depending on the fashion of the time.

And how does the normate get established? Art. Depictions of characters in painting, film, sculpture, and photography have a huge impact on the bodily expectations, but the normate is also reinforced by the descriptions of characters in literature. Take another look at the Adonis description: can you think of any popular characters that fit that description, plus or minus the facial hair? Odysseus. Jason. Heracles. Romeo. Sherlock Homes (look it up--he's buff). James Bond. The Man with No Name. Rocky Balboa. Indiana Jones. Superman. Batman. Wolverine. Jack Sparrow. The Winchester Boys. The T-1000. John Snow. Mr. Clean. The guy on the Brawny paper towels. All fit the same basic description, and as they are our heroes, we will want to look like them, and thus the normate is reinforced.

Wait... isn't everyone's body different?

This is the central truth of affliction theory: nobody's perfect (well, almost nobody--we'll get there). Some people have noses that are very long or very short, some have huge feet, some have moles or freckles, and that's just the start of millions of imperfections a single person has. But wait--who says that these are imperfections? According to leading affliction theorist Rosemarie Garland-Thompson, every society creates what the ideal man and woman look like--for current American culture, this is the Adonis figure with his broad chest, muscular arms, chiseled abs, and (as of this moment) rough stubble that isn't a bare cheek and isn't a full beard. Note that this ideal body, which Garland-Thompson calls the normate, is culturally constructed and can change at any time; in the recent past, mustachioed, clean-shaven, and full-bearded men have been the normate depending on the fashion of the time.

And how does the normate get established? Art. Depictions of characters in painting, film, sculpture, and photography have a huge impact on the bodily expectations, but the normate is also reinforced by the descriptions of characters in literature. Take another look at the Adonis description: can you think of any popular characters that fit that description, plus or minus the facial hair? Odysseus. Jason. Heracles. Romeo. Sherlock Homes (look it up--he's buff). James Bond. The Man with No Name. Rocky Balboa. Indiana Jones. Superman. Batman. Wolverine. Jack Sparrow. The Winchester Boys. The T-1000. John Snow. Mr. Clean. The guy on the Brawny paper towels. All fit the same basic description, and as they are our heroes, we will want to look like them, and thus the normate is reinforced.

SOMETHING'S OFF: Determining impairment

So any person falling outside the normate is The Other, right? Not exactly. Remember, social lens all have an other that lacks agency, or the ability to make one's own choices. In the case of affliction theory, this means lacking the literal physical ability to do something that the normate can do easily. A character with a large nose, crooked teeth, and freckles may not fit the Adonis model, but he can do everything the normate can do, so they are not the Other. But if the person has a serious impairment--a physical illness, injury, or deformity--that prevents them from functioning in the world in the same way as the normate, then they are The Other. Take Tiny Tim of A Christmas Carol: his crippled leg makes it so he cannot walk without a crutch. Impairments can be temporary: Pip in Great Expectations is temporarily impaired by a sickness, and Jem is impaired at the end of To Kill a Mockingbird by a broken arm. Some impairments can limit more than physical abilities: Cyrano de Bererac, Magawisca of Hope Leslie, and Quasimodo of The Hunchback of Notre Dame all struggle with finding someone to love them in spite of their long nose, missing arm, and... well, hunchback, respectively. Age can also be an impairment: Don Quixote's advanced age makes it very difficult for him to carry out all the feats of a knight errant. Affliction can also be mental, yet not all mental problems are physical impairments. A character that has low confidence because their father berates them doesn't have an impairment, but characters like Bertha Mason in Jayne Eyre or Benjy Compson in The Sound and the Fury are impaired, as they have abnormal mental faculties.

There are some physical features that do not count as impairments, and many of these bodily issues are handled by other lenses. Skin color, for example, is a feature that may rob a character of their agency but is not an impairment; take Othello--he is a capable and talented soldier who is able to do more than most men, so he is not impaired, but his skin color robs him of his agency according to postcolonialism. Similarly, a woman who does not conform to the female normate (the Venus figure) may have an impairment, but feminism examines a woman who lacks agency simply because her body is not male. Intersexed and transsexual characters may have been born with a body that doesn't match their identity, but this is covered by queer theory. The way a body is exhausted from work as an economic commodity falls into Marxism. Anthropomorphized nonhuman characters who want to be human--like Puss in Boots or the dog Enzo from The Art of Racing in the Rain--are not impaired by their nonhuman bodies: affliction theorists would compared them to the normate of their species, thus their struggle is explored through ecocriticism (a human character that is struck by an affliction that gives them features of an animal, like a werewolf or the Prince in "Beauty and Her Beast," is afflicted by an impairment and would be covered by affliction theory). Now this isn't to say that some characters aren't intersectional between two lenses: for example, Tom Robinson of To Kill a Mockingbird lacks agency both because he is Black (postcolonialism), he is poor (Marxism), and he has a withered arm (affliction theory).

Occasionally, afflictions work in the opposite direction: a boon is a physical abnormality that makes a character seen as superior to the normate. A good example is Superman: he is afflicted with flight, super-strength, freeze breath, and laser vision, all of which make him superior to the average person. However, he can still be considered the Other, as his powers make him and his loved ones a target of super criminals. Increasingly in both the real world and science fiction, cybernetic elements added to characters act as a boon. Some characters are afflicted with both a boon and impairment (like Tiresias, who is physically blind yet knows the future), and a single affliction can be both a blessing and a curse (like Cassandra's ability to see the future but her inability to convince anyone of her visions). These character, called supercrips, are common in classic literature and are typically used to challenge the notion of disability. Supercrips are commonly used in the superhero genre, where characters like Cyborg and the Thing are physically changed by their powers and struggle with fitting into normal society, yet even characters that seem to fit the normate can be supercrips. Superman regularly struggles with how the alien physiology that makes him so powerful also prevents him from aging with his wife Lois Lane and even fathering children with her.

There are some physical features that do not count as impairments, and many of these bodily issues are handled by other lenses. Skin color, for example, is a feature that may rob a character of their agency but is not an impairment; take Othello--he is a capable and talented soldier who is able to do more than most men, so he is not impaired, but his skin color robs him of his agency according to postcolonialism. Similarly, a woman who does not conform to the female normate (the Venus figure) may have an impairment, but feminism examines a woman who lacks agency simply because her body is not male. Intersexed and transsexual characters may have been born with a body that doesn't match their identity, but this is covered by queer theory. The way a body is exhausted from work as an economic commodity falls into Marxism. Anthropomorphized nonhuman characters who want to be human--like Puss in Boots or the dog Enzo from The Art of Racing in the Rain--are not impaired by their nonhuman bodies: affliction theorists would compared them to the normate of their species, thus their struggle is explored through ecocriticism (a human character that is struck by an affliction that gives them features of an animal, like a werewolf or the Prince in "Beauty and Her Beast," is afflicted by an impairment and would be covered by affliction theory). Now this isn't to say that some characters aren't intersectional between two lenses: for example, Tom Robinson of To Kill a Mockingbird lacks agency both because he is Black (postcolonialism), he is poor (Marxism), and he has a withered arm (affliction theory).

Occasionally, afflictions work in the opposite direction: a boon is a physical abnormality that makes a character seen as superior to the normate. A good example is Superman: he is afflicted with flight, super-strength, freeze breath, and laser vision, all of which make him superior to the average person. However, he can still be considered the Other, as his powers make him and his loved ones a target of super criminals. Increasingly in both the real world and science fiction, cybernetic elements added to characters act as a boon. Some characters are afflicted with both a boon and impairment (like Tiresias, who is physically blind yet knows the future), and a single affliction can be both a blessing and a curse (like Cassandra's ability to see the future but her inability to convince anyone of her visions). These character, called supercrips, are common in classic literature and are typically used to challenge the notion of disability. Supercrips are commonly used in the superhero genre, where characters like Cyborg and the Thing are physically changed by their powers and struggle with fitting into normal society, yet even characters that seem to fit the normate can be supercrips. Superman regularly struggles with how the alien physiology that makes him so powerful also prevents him from aging with his wife Lois Lane and even fathering children with her.

WILLING BUT UNABLE: Exploring disability

While the term impairment is used for the physical affliction affecting a character, disability refers to when a character's impairment keeps them from overcoming an obstacle the normate can easily counter. An impairment is something a character has, while a disability is something a character encounters. For example, Lennie in Of Mice and Men encounters a moment of disability when, because of his mental inability to regulate his own strength, he breaks the neck of his rabbit from petting it too hard. Sometimes, disability is more than a moment: once Oedipus stabs out his own eyes, he struggles with blindness from then on. Yet not every chronic impairment is a constant disability: John Singer from The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is deaf, yet most of the time his impairment does not result in disability and he navigates the world well. The opposite can also be true--a character can fall into a sick role where, once they are diagnosed with an affliction, the character assumes disability regardless of their actual ability--they live up to the role of an invalid and rob themselves of their own agency. A good example of this is Laura from The Glass Menagerie: while her childhood bout with pleurosis left her with a slight limp, she continues to believe that she is deformed and unable to hold down a job or find a boyfriend when she is capable of both.

Speaking of agency, affliction theorists tend to focus on how characters with impairments are robbed of their agency by both moments of disability and those who make assumptions about the character based on their impairment. Take Quasimodo: he struggles with his deafness as he communicates with other characters (moment of true disability), but he is also isolated from others by Claude Frollo because Frollo assumes that Quasimodo's appearance and impairments mean that he cannot live a normal life amid the normate citizens of Paris (moment of imposed disability).

Speaking of agency, affliction theorists tend to focus on how characters with impairments are robbed of their agency by both moments of disability and those who make assumptions about the character based on their impairment. Take Quasimodo: he struggles with his deafness as he communicates with other characters (moment of true disability), but he is also isolated from others by Claude Frollo because Frollo assumes that Quasimodo's appearance and impairments mean that he cannot live a normal life amid the normate citizens of Paris (moment of imposed disability).

This dynamic between true and imposed disabilities isn't new or even limited to fiction. The history of how societies in the real world dealt with disability can be broken into three distinct periods:

The way that affliction theorist look at how disability is depicted in a text reflects this history. Unlike most minority groups, the afflicted tend to be well represented in literature, yet their representation isn't always positive. Typically, the afflicted are included in a story for narrative prosthesis, or the inclusion of an affliction as a shorthand for characterization or as a story metaphor. Ernst Blofeld in the James Bond series has a large scar and is blind in one eye: this affliction makes him frightening looking and serves as characterization, making him more wicked. Another blind character, Oedipus stabs his eyes out after realizing he married and fathered children with his mother; this affliction acts as a story metaphor, as he finally "sees" the truth. Tiny Tim can barely walk, which underscores his family's poverty. While narrative prosthesis can give characterization to the afflicted character, it also gives characterization to characters that are not afflicted by contrast. Magawisca competes with Hope Leslie for Everett's affection, yet Magawisca's missing limb characterizes her as damaged, thus Hope is defined as pure by contrast. The ugliness of Quasimodo serves to highlight the beauty of Esmeralda in comparison.

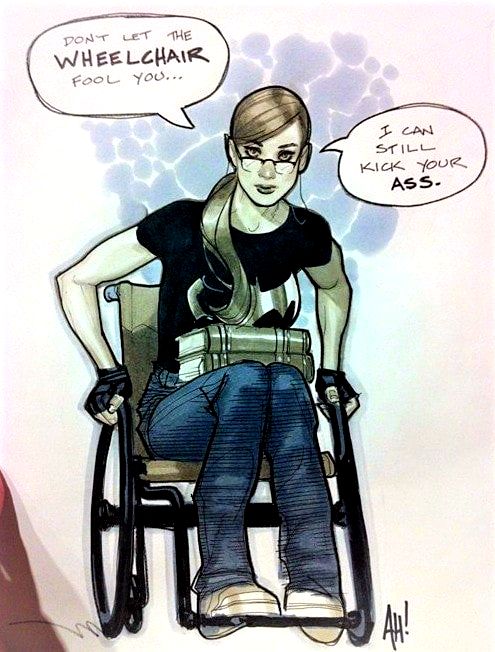

Afflicted characters are usually defined by their single stigmatic trait: instead of a character with blindness, they are a blind character, meaning their blindness overtakes who they are. Tiresias is defined as the blind poet, Mary Ingalls is characterized as the blind sister in the Little House on the Prairie series, and Blind Pew in Treasure Island literally has blind in his name. For affliction theorists, these are negative depictions, as the impairment comes to dominant the character even when they do not struggle with disability. Positive depictions involve a well-rounded character that only focuses on their affliction in times of disability, or they involve depictions of a character embracing their affliction as an important part of their identity (this is called enfreakment). While enfreakment is more typical when the affliction is a boon, it can also apply to impairments that characters struggle against. In Moby Dick, the titular whale bit off Ahab's leg and Ahab struggles with the pain from his stump, yet in a moment of enfreakment, he gives himself a peg leg of whale bone to prove that a whale won't destroy him--that he'll destroy the whale.

- THE SYMBOLIC PERIOD (The beginning of recorded history to the Scientific Revolution): For most of human history, the causes behind impairments and other afflictions were unknown, so people attributed illness and physical deformities to the actions of the gods. Sometimes, an affliction was a blessing (a gift from the gods, like Orpheus's musical ability), but afflictions were usually seen as punishment from the gods for a sin or moral failing.

- THE MEDICAL PERIOD (The Scientific Revolution to the Civil Rights Movement): Eventually, advances in medicine and biology revealed that illness is caused by bacteria and viruses and deformities are the result of genetic chance or accident. During this period, society attempted to either cure a person of their affliction, isolate them so no one would need to encounter their illness, or simply end their life. This belief that the afflicted are inferior to the normate is called ableism and is still felt in social policies today. While this cure-cover-kill approach seems drastic, much of this period was influenced by eugenics, or the belief that humans could and should be bred to only have the best characteristics--those that match the normate.

- THE SOCIAL PERIOD (Post-Holocaust to today): While curing illness is still seen as a noble cause, the idea that the afflicted should be isolated from society or killed is monstrous, as demonstrated by the brutality of eugenics experiments like the Holocaust, where Jews, homosexuals, the physically handicapped, and others were systematically murdered. In Birth of the Clinic, philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the medical community actually robbed people of their agency, as they would try to "fix" the afflicted to conform to normative bodies. Foucault and later theorist instead called for afflicted people to be integrated into larger society and to be valued for what they can do over what they cannot.

The way that affliction theorist look at how disability is depicted in a text reflects this history. Unlike most minority groups, the afflicted tend to be well represented in literature, yet their representation isn't always positive. Typically, the afflicted are included in a story for narrative prosthesis, or the inclusion of an affliction as a shorthand for characterization or as a story metaphor. Ernst Blofeld in the James Bond series has a large scar and is blind in one eye: this affliction makes him frightening looking and serves as characterization, making him more wicked. Another blind character, Oedipus stabs his eyes out after realizing he married and fathered children with his mother; this affliction acts as a story metaphor, as he finally "sees" the truth. Tiny Tim can barely walk, which underscores his family's poverty. While narrative prosthesis can give characterization to the afflicted character, it also gives characterization to characters that are not afflicted by contrast. Magawisca competes with Hope Leslie for Everett's affection, yet Magawisca's missing limb characterizes her as damaged, thus Hope is defined as pure by contrast. The ugliness of Quasimodo serves to highlight the beauty of Esmeralda in comparison.

Afflicted characters are usually defined by their single stigmatic trait: instead of a character with blindness, they are a blind character, meaning their blindness overtakes who they are. Tiresias is defined as the blind poet, Mary Ingalls is characterized as the blind sister in the Little House on the Prairie series, and Blind Pew in Treasure Island literally has blind in his name. For affliction theorists, these are negative depictions, as the impairment comes to dominant the character even when they do not struggle with disability. Positive depictions involve a well-rounded character that only focuses on their affliction in times of disability, or they involve depictions of a character embracing their affliction as an important part of their identity (this is called enfreakment). While enfreakment is more typical when the affliction is a boon, it can also apply to impairments that characters struggle against. In Moby Dick, the titular whale bit off Ahab's leg and Ahab struggles with the pain from his stump, yet in a moment of enfreakment, he gives himself a peg leg of whale bone to prove that a whale won't destroy him--that he'll destroy the whale.

SO HOW DO I READ LIKE AN AFFLICTION THEORIST?

Affliction theorists focus on how character manage afflictions (both boons and impairments) and how other characters treat them because of their affliction.

- An affliction theorist determines what the normate is and which characters deviate from the normate. What does the ideal man or woman look like? What are they able to do? What characters have extraordinary powers above the normate? What characters have impairments?

- An affliction theorist looks for moments of disability. When does the impairment present an obstacle to the character? How do they overcome their moment of disability? Do they require outside help, and how do they get it?

- An affliction theorist examines how characters are treated because of their affliction. Is a character defined by their impairment? Do other characters treat them differently or have preconceived notions about them? Are the characters feared, derided, or isolated because of their because of their affliction?

- An affliction theorist also examines how characters think of themselves based on their affliction. Does the character define themselves by their affliction? Do they let the affliction take over and play a sick role? Are they ashamed of their affliction, or do they celebrate it in an act of enfreakment?

- An affliction theorist considers the narrative purpose of giving the character the affliction. What narrative purpose is served by giving the character this affliction? Is it necessary for conflicts in the plot? Does the affliction serve to define a character? Is the affliction symbolic of a larger theme or motif?

THE BREAKDOWN

- Affliction theory focuses on bodies that fall far outside the ideal (the normate)

- Look for characters with impairments that make them "less than"

- Look for characters with boons that make them superhuman

- Look for how a character approaches moments of disability

- Look at how characters react to their affliction: do they embrac the sick role or embrace enfreakment?

- Look at how characters are treated by others because of their affliction

- Look for a symbolic or metaphoric meaning behind the nature of the affliction

GREAT TEXTS TO READ FROM AN AFFLICTED LENS

- Oedipus Rex by Sophocles

- The Iliad by Homer

- Richard III by William Shakespeare

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

- The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux

- Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand

- The Hairy Ape by Eugene O'Neill

- The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

- The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams

- The Lord of the Flies by William Golding

- Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

- Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer

- The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

- A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

FURTHER CRITICAL READING

Davis, Lennard. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body. Verso, 1995.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (1963), translated by Alan Sheridan Smith. Vintage, 1994.

Garland-Thompson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Colombia University Press, 1996.

Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Mitchell, David T. Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse. University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Shakespeare, Tom. "The Social Mode of Disability". The Disability Studies Reader, Fourth Edition, edited by Lennard Davis. Routledge, 2013, pp. 214-221.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (1963), translated by Alan Sheridan Smith. Vintage, 1994.

Garland-Thompson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Colombia University Press, 1996.

Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Mitchell, David T. Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse. University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Shakespeare, Tom. "The Social Mode of Disability". The Disability Studies Reader, Fourth Edition, edited by Lennard Davis. Routledge, 2013, pp. 214-221.